Attribution

Much of the content from these notes is taken directly or adapted from the notes of the same course taught by Dr. Andrew Forney available at forns.lmu.build.

Introduction

In this lecture, we’re going to focus on a specific application of dynamic programming: the Longest Common Subsequence (LCS) problem.

Take a look at the following two strings:

GTACAC

GACATG

Question

What’s interesting about these strings?

They have a decent amount in common with one another — not just in the letters themselves, but also the order in which they occur. They also represent parts of a genetic sequence!

In genetic analysis, it’s often important to find commonalities in gene sequences for closer examination, but genes are not perfect and the coded sequences are subject to noise:

- Genes themselves can have tiny amounts of corruption/noise that prevent finding perfect sequential matches.

- Genes are spliced imperfectly, and we may only find partial matches at different parts of each string.

It turns out that dynamic programming is commonly applied for this very scenario!

In the Longest Common Subsequence (LCS) problem, we are given two strings and and we want to find the longest sequence of characters that both strings possess in the same order (left to right), though not necessarily in contiguous blocks.

Question

What is the LCS of the strings

"AXBYCZ"and"SATBCU"?

The LCS of these two strings is "ABC" since that is the longest sequence of letters that can be found in both strings, even though there may be other letters in between.

On the surface, this seems like a pretty easy problem, but it can be tricky because we don’t always initially know where in each string the longest subsequence is going to begin.

Consider the following tricky case:

ABCDABADE

^^ ^^^ ^^

ACBDACBDE

^ ^^^ ^^^

The LCS of these two strings is "ABDABDE", but note that there are many different potential-longest substrings, and we need to find the best.

We can start to think about applying our dynamic programming tools to sift through these possibilities, beginning with one key property: the LCS problem exhibits the optimal substructure property.

Question

How does the LCS problem exhibit the optimal substructure property?

Consider the simple case of lcs("ABC", "ABC"). In order to know that "ABC" is the LCS of these two strings, we can observe that the LCS of any prefix can be added to the LCS of any postfix such that:

In other words, we want to compare all pairs of subsequences between the two strings, finding the maximal-length subsequences between each.

Now that we’ve identified this as a problem with optimal substructure, let’s think about how we might solve it with both bottom-up and top-down dynamic programming.

Formalizing LCS as DP

As with the ChangeMaker problem, we can envision an approach to solving LCS through the lens of search before thinking about how to formalize it as a dynamic programming problem.

Let’s think of the pieces that would look search-like here:

- State: We have two strings composing the state, and , as in the arguments to the LCS method:

lcs(R, C). - Initial State: and with all original letters in each.

- Terminal State: At least one of or reduced to the empty string

""(because the LCS of anything and an empty string is empty too). - Actions/Transitions: Work toward the terminals one letter at a time:

- Examine the last letter in each of and at one state:

- If they match, they might be part of the LCS, so pair them up, add them to that path’s LCS, remove them from both and , and continue on the remainder of each.

- If they mismatch, the LCS must ignore one or the other, so branch and take the max length subsequence of the children.

- Examine the last letter in each of and at one state:

Consider what this would (conceptually) look like in a search-like tree on the subproblem lcs("AXB", "ABX"):

Question

What is/are the solution(s) to the subproblem above?

The LCS will be of length 2, either "AX" or "AB".

Now, let’s consider how this tree-based representation maps to our dynamic programming.

LCS Memoization Table & Ordering

To help us think about the table, let’s first have a motivating example and use that to answer some targeted questions.

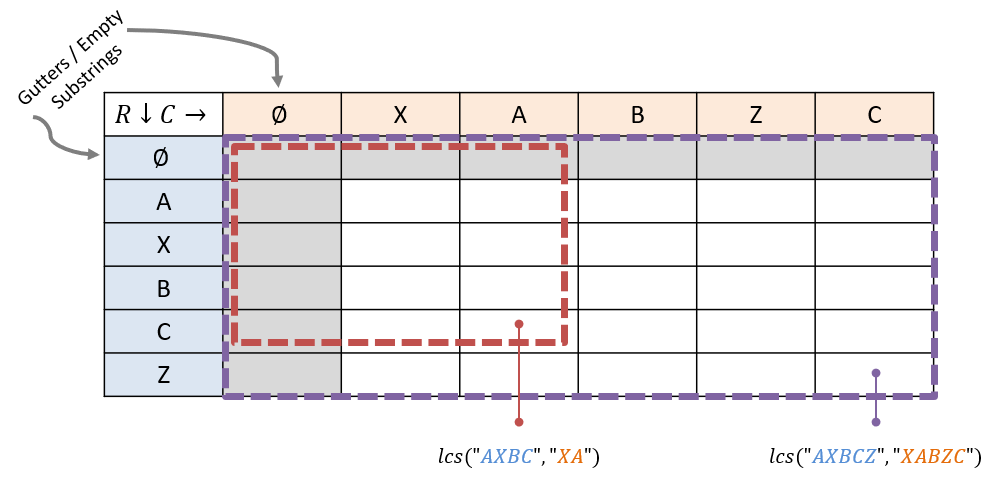

Consider the memoization table that would be associated with the problem lcs("AXBCZ", "XABZC") in the questions that follow.

Question

Compared to

lcs("AXBCZ", "XABZC"), what would a smaller subproblem look like, and how does that map to the ordering of problem-specific rows/columns?

We can think about each row/column adding a new letter to the substring of previous rows/columns in left-to-right order. Note that this is a lot like ChangeMaker where each row added a new coin denomination compared to the row before it.

Question

What are the SMALLEST two substrings we could solve (think: top-left of the table)?

Kind of a trick question: the empty strings! These will constitute so-called “gutters” of the memoization table that will be convenient for the recurrence’s base cases.

Question

What should be recorded in the table’s cells (data type and purpose) to find the LCS of two strings?

Cells contain the number of strings (integer) of the longest common subsequence, which can then be traced back to recover the actual string just like in ChangeMaker!

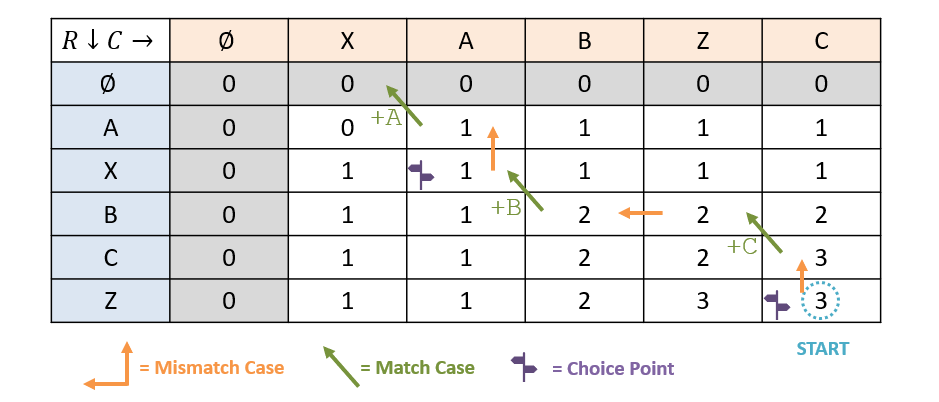

Draw and then interpret the memoization table that would be used in solving lcs("AXBCZ", "XABZC"):

Some things to note about the table:

- Any given cell will find the LCS of the substring of all previous rows/columns that came before it (see optimal substructure highlighted in red box above).

- The solution to the original, full problem will (per usual) be located in the bottom-right of the table.

- There may be multiple solutions to each LCS problem, each equally valid.

Question

What possible solutions are there to the LCS problem posed above? (hint: there are 4)

lcs("AXBCZ", "XABZC") = "ABC" = "XBC" = "XBZ" = "ABZ".

As such, we should be sensitive that, if we are simply looking for a single solution, then any one of maximal length will suffice, but we could also use this approach to collect all solutions (left as an exercise)!

With the table format specified, let’s consider how to fill it out.

Completing the Table

We want to record the length of the LCS in the substrings associated with each cell’s row and column. Then, we can “walk back” a solution from the bottom-right of the table.

First, some notation:

- Let index correspond to letters in the string along the rows and index of letters in the string along the columns.

- As such, would represent the new letter added to substring before , with the special case of . E.g., if

"AXBCZ", ,A,X, etc. - The answer to any cell of the table can be expressed as .

Let’s start with the easy cells to complete: the base cases.

Question

Which cells will we know the answers to at the start without having to do any sort of computation?

The gutters! The LCS of any string with the empty string must be of length 0!

Case 0 - Base Case

The LCS of any string with the empty string

""must be 0, formally:

For the rest of the table (i.e., between two non-empty strings), we can focus on the newly added letter at each row and column substring.

To figure out the value of , we can look at the newly added letter at and and see if they are the same or different.

- If they match, pair them up and move on to the rest of the substring.

- If they don’t, the LCS must ignore one (or both) of them, so consider each branching path.

This is pretty much exactly the distinction between our branching vs. non-branching children in the search-tree intuition above!

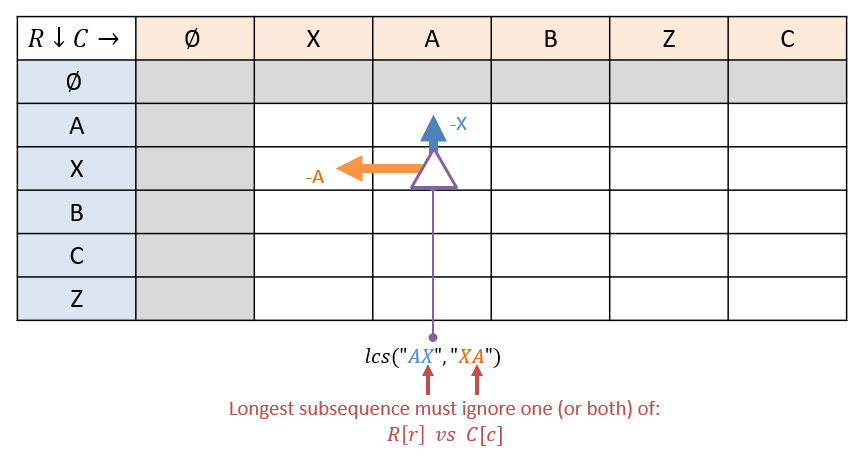

Case 1 - Mismatched Letters

When the letters at a given row and column disagree, these are the max nodes in our tree-based conceptual understanding requiring that we:

- Take the max of ignoring each of the letters individually.

- Phrase this “ignoring” operation as a function of smaller subproblems (again, must be above or to the left of ).

Given that we’re after the longest common subsequence, the rule to decide the value of the cell when the two letters disagree is:

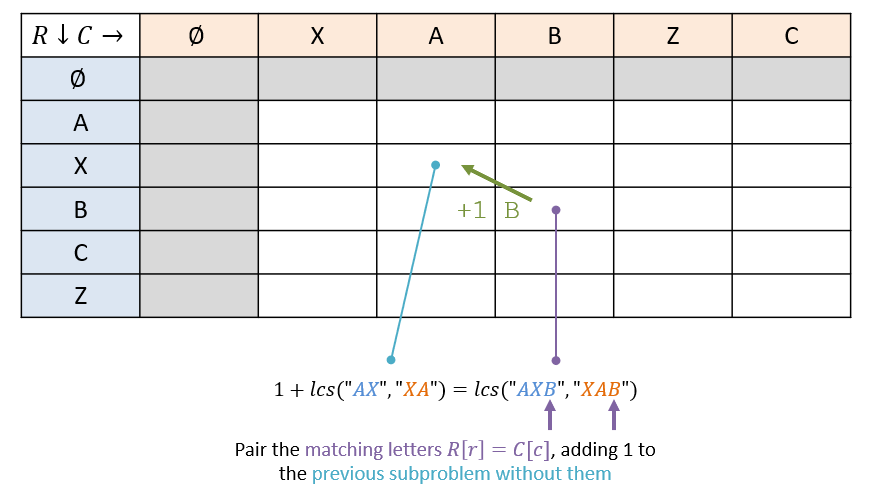

Case 2 - Matched Letters

When the letters at a given row and column agree, then we can add 1 letter to the LCS of whatever the LCS was to the prefixes before the match.

To fill a cell , where , the cell has the LCS of “whatever the LCS was to the prefixes before matching at row and column ” — the cell diagonally up and to the left of the matching cell.

The rule to decide the value of the cell when the two letters match is:

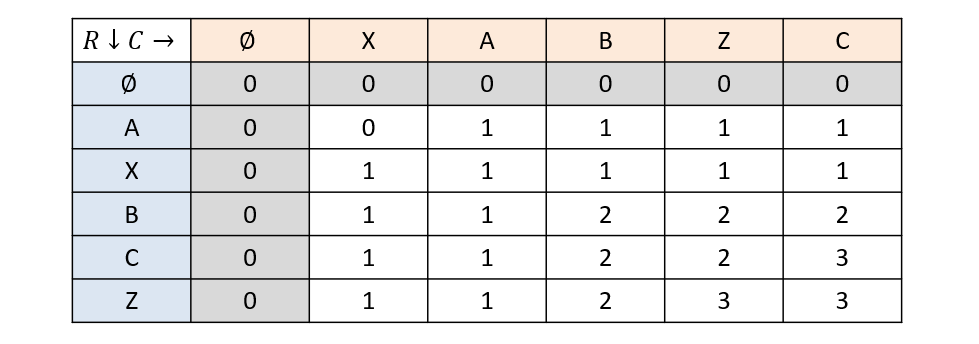

Bottom-Up LCS

With these rules in place, let’s fill out our table!

Examining the result above, we can note a couple of facts:

- The bottom-right cell will have the maximal number of letters in the LCS to the original problem.

- There may be clues to either side of each cell that tell which letters were added to the LCS along a given path, and which were not.

Constructing a Solution

Since we now have the complete memoization table in hand, constructing an actual LCS string is not difficult. We start at the bottom-right of the table and then walk backwards to our solution.

Remember that there may be multiple solutions that exist to the LCS problem.

The steps are as follows:

- Start at the bottom-right cell of the table.

- Undoing Case 1 (Mismatched Letters): If , then or , so recurse to the cell that has the same value.

- Note: if both adjacent cells have the same value as the current, either one is acceptable to recurse to.

- Undoing Case 2 (Matched Letters): If , then collect that matched letter as part of the LCS, and then recurse on the top-left cell, .

Some things to note here:

- We know we’re done collecting our solution as soon as we hit a base case: the gutters.

- Since we’re collecting the LCS letters from the bottom-right, the subsequence we assemble will be in reverse order, and must simply be flipped after collection.

- There were several choice points in the path we took wherein we could have chosen a different path to get a different (but equally valid) solution. To collect all possible solutions to an LCS problem, we would recurse at all choice points.

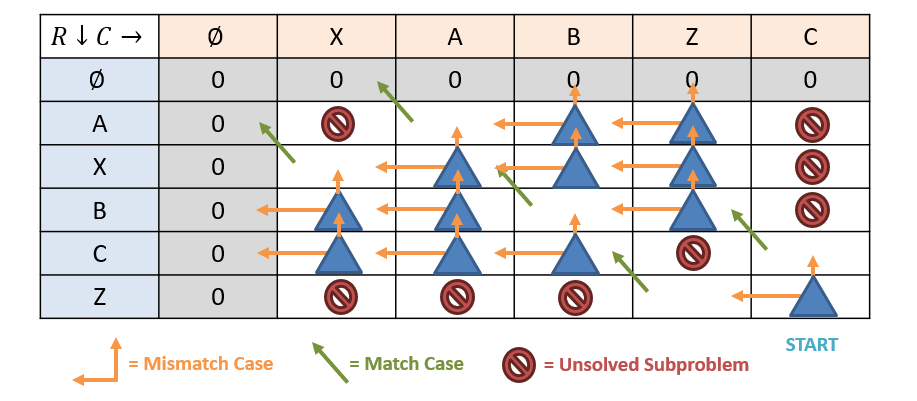

Top-Down LCS

Now let’s take a look at the top-down approach. We use the same memoization structure and recurrence in the top-down approach, but might be able to save some work by specifically targeting only the subproblems we need.

The steps are:

- Start at the largest subproblem (bottom-right of table) and identify which recurrence case is needed to solve it.

- For each cell needed by that recursion case, draw an arrow from the cell that needs the subproblem to the one that has the answer.

- In a depth-first fashion, you’ll discover the value in any cell when all outbound arrows from it have those cells/subproblems solved.

Question

Where, in the table above, do solutions to the overlapping subproblems save computation?

Whenever two arrows point into the same cell! One of these arrows/recursive calls will have had to compute the answer, and the other will simply find it waiting there.

We trace the needed subproblems to solve each cell, which would eventually give us the following table: