Attribution

Much of the content from these notes is taken directly or adapted from the notes of the same course taught by Dr. Andrew Forney available at forns.lmu.build.

Introduction

Let’s revisit the problem of changemaking, which you may have seen in CMSI 186. The problem is specified as follows: given a set of coin denominations and some sum of money to make change for , we must find the optimal (i.e., minimal) number of coins by which to make the requested amount.

Real-World Applications

This may seem like a toy problem, but it belongs to a class of problems called Knapsack Problems that are used everywhere, including: generations of keys in cryptography, maximizing investments in stocks, and finding the best set of loot to sell in video games given a limited inventory.

A Greedy Approach

For optimal change-making, we in the US are quite lucky, since the algorithm to accomplish it is very simple.

Question

If we were to compute the change for $0.81 with the standard US currency, how would we go about this?

We would simply take the largest denomination from the amount remaining, then recurse on the rest.

This strategy works for US coin currency and is simple to implement! Strategies that always take the next “best” action available at any state are called greedy strategies. The greedy strategy works out for US currency in change making, but is that true for all currencies?

Greed is (Sometimes) Bad

Consider a currency with denominations and we wish to make change for cents.

Question

What will the greedy approach return as the solution to the changemaking problem for cents? Is this the optimal amount?

The greedy approach will return coins: , but this is not optimal! We could have made cents with coins: .

So it would seem that the greedy method does not always return the optimal solution for changemaking, depending on the input denominations.

Let’s try to think of the changemaking problem in terms of a search problem.

Searching for Change

Let’s think about the changemaker problem as a search problem and note some its interesting properties.

The Changemaker Search Problem can be defined as follows:

- Initial State: amount of cents remaining to make change for.

- Goal State: cents left.

- Actions: give a coin from amongst the denominations that are less than the amount remaining in the state.

- Transitions: subtract that coin’s value from the state.

- Cost: uniform cost, per coin given.

Take a second to appreciate how what we’ve been learning is applicable to other problems. Now that we’ve formalized our problem in terms of search, we can make use of the algorithms we’ve learned to solve it!

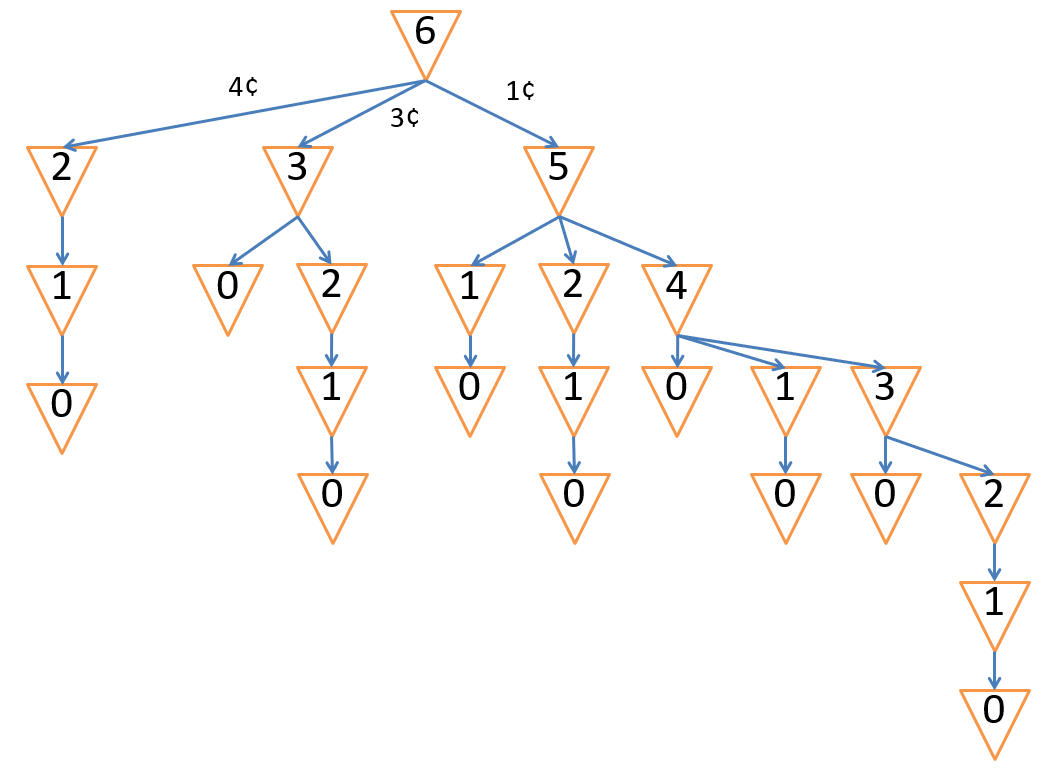

Let’s start by drawing the search tree of the Changemaking Problem.

Note on Min Nodes

The min nodes above are used to signify the “minimum number of coins,” not anything like utility or change amount like we saw with Minimax search.

Question

How is the Changemaking search tree different than the Maze Pathfinding search tree that we had been examining originally?

The actions along a path to a goal matter, but crucially, their order does not.

Believe it or not, this is a really big difference:

- In Changemaking: taking .

- In Pathfinding: taking (there might be walls or mud tiles avoided in one path that isn’t in another).

Question

Why is this property significant? Does it pose any challenges we might have an idea how to solve?

This property leads to far more repeated states and extraneous paths that might get explored. Intuitively, we would like to use memoization, or caching, to reduce the amount of repeated work.

In order to use caching on this search tree, we need to know the solution to the sub-problem that we’re memoizing.

Question

What search strategy does this suggest we use?

We should use depth-first search so that we can reach terminal states more quickly, and therefore cache more sub-problem solutions that we are more likely to encounter in this setting.

Reflect

Why would Breadth-first Search not scale well in problems like these, even though it appears to be a good strategy above?

Observe the left-most subtree in our full search tree. In order to cache the state with cents remaining, we must reach the terminal state coins below it, which is why it makes sense to use DFS here.

Once we’ve cached that state, observe how many other times we save ourselves from having to recompute it:

The application of memoization in this context is actually a special case of a broader programming paradigm called Dynamic Programming.

Dynamic Programming

Dynamic Programming is another programming paradigm where solutions to large problems are found through recursive decomposition into smaller, more easily solved, problems.

These problems are characterized by two properties:

- Optimal Substructure: the optimal solution to the big problem is a function of the optimal solutions to its sub-problems.

- Overlapping Sub-problems: the solutions to the same sub-problems are required multiple times while solving larger sub-problems.

This is a similar idea to “divide and conquer” algorithms you might have seen elsewhere (like Merge and QuickSort), but D&C algorithms do not always have the properties above.

Optimal Substructure Intuition

Consider the case where we have our optimal set of coins for the Changemaking problem where such that:

The optimal substructure property can be interpreted this way: removing a coin from will provide the optimal solution to the problem:

Testing that out:

In other words, take a coin from the optimal solution to a CM problem, and you’ll have the optimal solution to that amount minus the value of the coin removed.

A nice property of problems with optimal substructure is that they can be represented as a recurrence.

Question

How would you represent the solution to the th Fibonacci number, , as a recurrence?

if (the base case), otherwise (the recursive case).

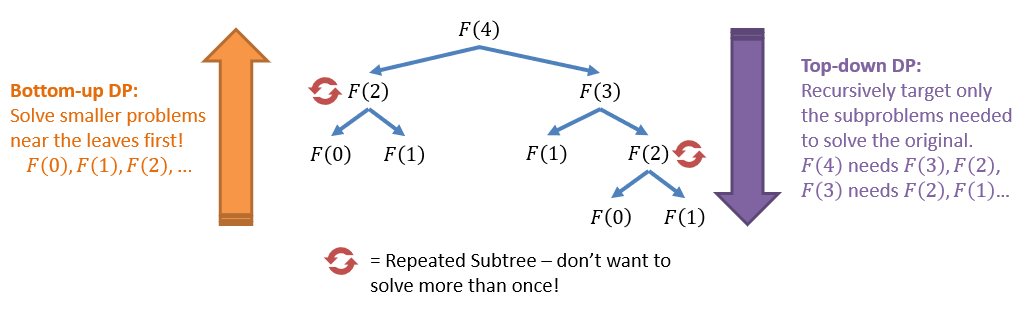

Types of Dynamic Programming

Even a recurrence as simple as Fibonacci can be solved in a couple of different ways, each with their own pros and cons.

We can visualize the Fibonacci sequence and the sub-problems that would be needed to solve each piece:

Because of the optimal substructure requirement, there are two main approaches to dynamic programming:

- Bottom-up Dynamic Programming (Tabulation): solves the smallest sub-problems first, then uses those solutions as the foundation on which to build up to larger and larger sub-problems.

- Top-down Dynamic Programming (Memoization): start with the large problem, then recursively identify specific sub-problems to solve.

If we wanted to compute the th number in the Fibonacci sequence, i.e., , the bottom-up approach would begin by solving: .

This is reasonable because , so having the earlier entries pre-computed means we have them immediately available as stepping-stones into the later entries.

If we wanted using the top-down approach, we would start by knowing that , at which point we would recursively call the function on each of the smaller sub-problems, caching those that we had already computed along the way.

Let’s take a closer look at the differences between these two approaches and when one might be preferable to the other.

Bottom-up Dynamic Programming

To recap, the gist of bottom-up dynamic programming on the changemaker problem is as follows:

- Start with the smallest denomination and find the best ways to make incrementally increasing sums of change up until the desired sum, .

- Repeat for larger denominations by checking if the combination of larger denominations is better than the combination found for smaller denominations.

- Once this has been done for all denominations, we can use the results to find the optimal combination of coins.

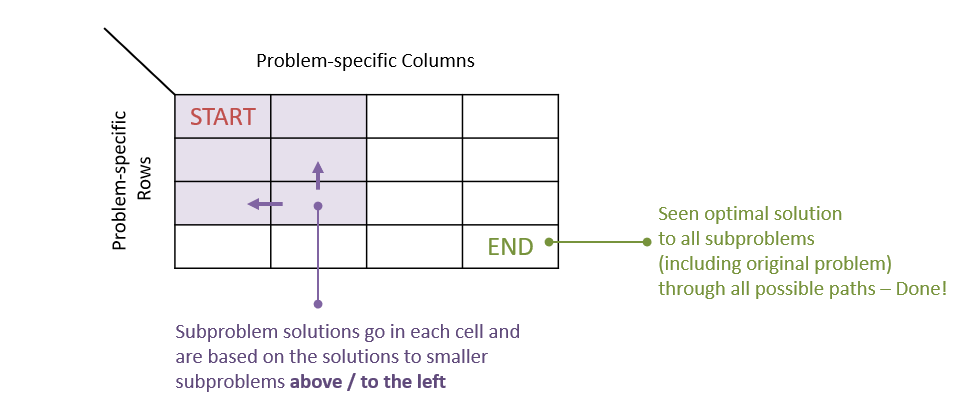

Most dynamic programming approaches rely on specifying two key components:

- Memoization Structure: a data structure chosen to represent the previously computed sub-problems. Typically these are tabular (i.e., a table / matrix / 2D array).

- Ordering: choose an ordering of rows / columns such that a larger sub-problem is never computed before a smaller one.

Bottom-up dynamic programming is often referred to as “Tabulation” because the memoization structure is so central to the algorithm.

Here, we can interpret the start and end locations of the table intuitively:

- Start: where we begin the operation with the optimal solution to the smallest sub-problem.

- End: where we end the operation with the optimal solution to the largest sub-problem / original problem.

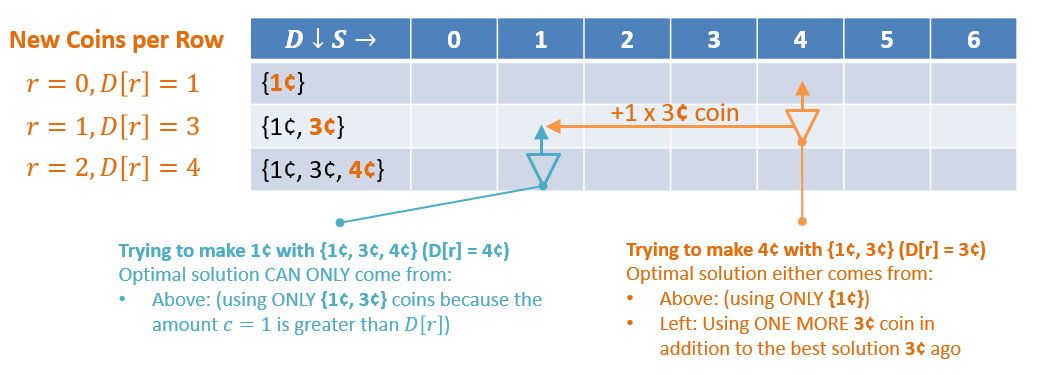

For the Changemaker problem, there is an intuitive mapping of the problem parameters to the table’s rows / columns:

- Columns: increasing change amounts to make, up to such that column , column , …, column .

- Rows: the different denominations.

Question

For the Changemaker problem, is there an intuitive ordering for the rows (denominations) and columns (sums) to satisfy the ordering criteria?

Yes! Columns: start with change then increase incrementally toward with each index. Rows: for this problem, it doesn’t particularly matter, but intuitively, we can sort by ascending denomination size.

Question

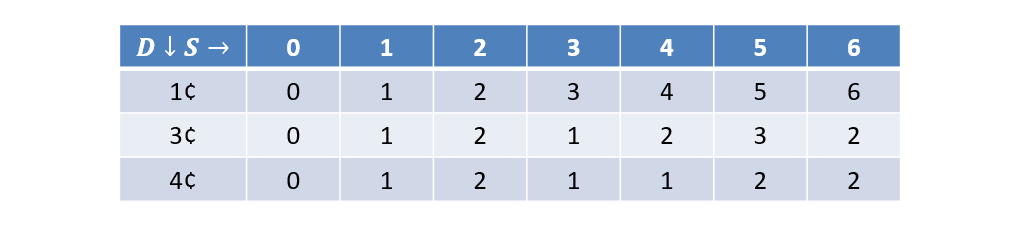

Construct the bottom-up DP table associated with the Changemaker problem with , .

Notes on the above:

- The notation refers to the value of the newly added coin denomination from the row above it. E.g., because the cent coin was the newly added denomination from the rows above it.

- Even though we’re just storing an integer in each cell denoting the optimal / minimal number of coins to solve each sub-problem, we’ll be able to reconstruct which coins compose the solution later.

- From here on out, we’ll focus on just at each row (and so drop the set notation), but can remember this interpretation for each row: trying to solve each sub-problem with a subset of coins.

Tabulation Mechanics

Question

Given that we plan to start with the smallest sub-problem in the top-left and end up with the solution to the largest problem in the bottom-right, how should we fill it out / complete it in a bottom-up fashion?

We’ll simply start at the top left and then go row by row, column by column finding the values in EVERY cell in the table.

This way, we guarantee that we’re never missing a better way to make that column’s amount of change because we’ll have already seen the best way to do it using smaller denominations.

For a given cell of the table , “smaller” sub-problems will either be:

- Above that cell, i.e., for some row less than = solutions that DO NOT use the new denomination .

- To the left of that cell, i.e., for some column less than = using one coin of the new denomination in addition to the remainder.

We can think of each cell as being a mini-min-node that asks: “Is the best way to make this column’s sum using a previous sub-problem’s solution (with a subset of denominations), or by using my row’s new coin?“.

Encapsulating the intuitions above into a recurrence:

- Recurrence: a recipe for completing a tabular memoization structure that has been organized such that larger sub-problem solutions can be phrased as a function of smaller sub-problem solutions. This gives us an algorithm for determining the contents of any cell that decomposes to one of three cases for Table , coin denominations , row / denomination index , and column change remaining / index :

Let’s try that out and fill in the table:

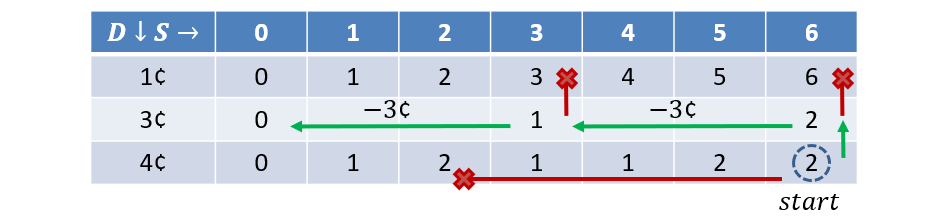

We can use the completed table to find the optimal solution by starting at the bottom-right of the table:

- If , then the optimal solution came from denominations above, so recurse on .

- Else, we used a coin from this denomination to get to , so collect that coin in our final solution then recurse on .

- Return the full solution of collected coins when .

Question

Suppose we have (number of denominations) and , what is the asymptotic runtime / space complexity of these tabular methods?

We have to compute each cell, so the time and space complexity is .

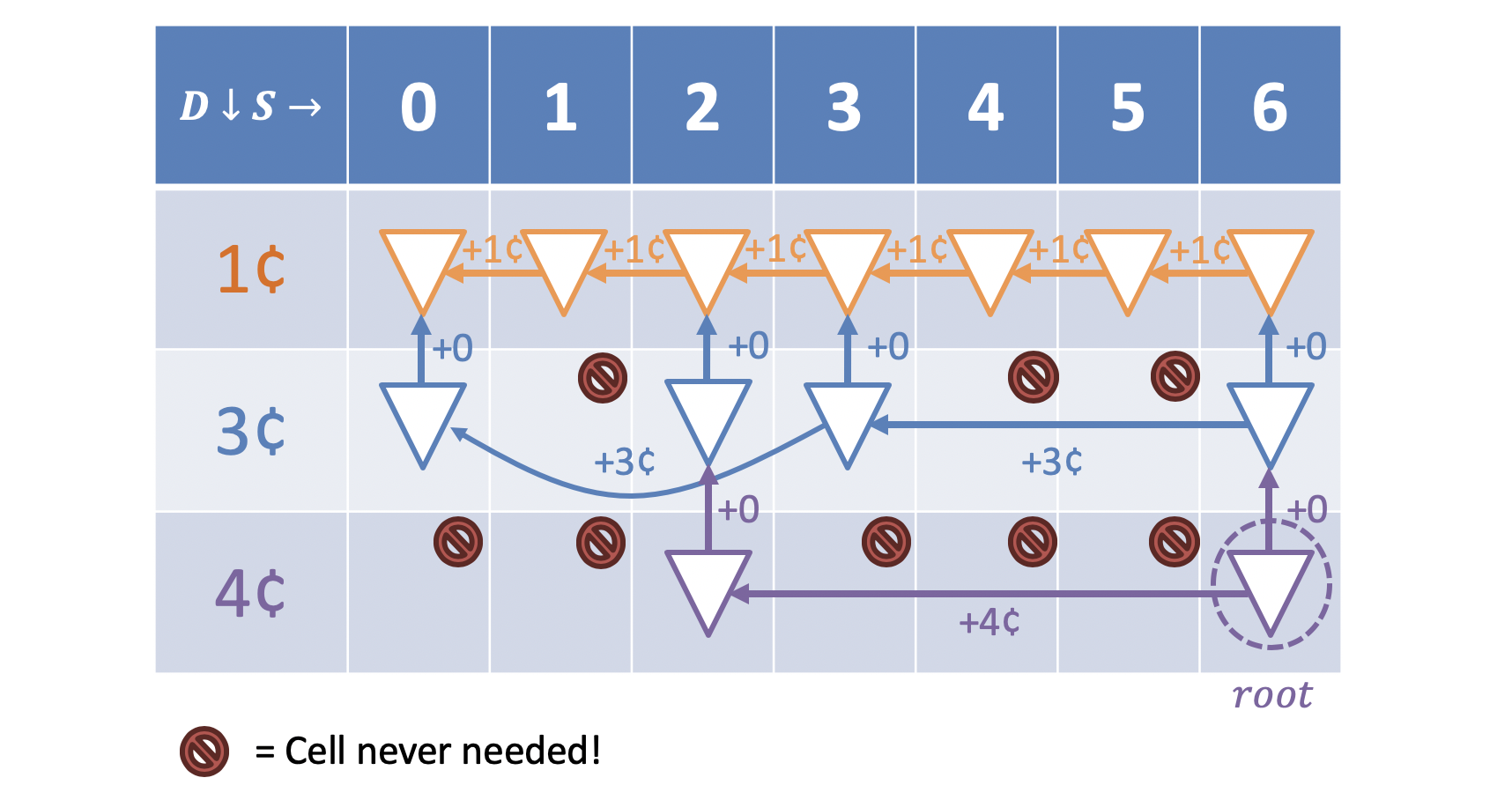

Top-down Dynamic Programming

Using the bottom-up approach, you may have noticed that many cells were completed unnecessarily. This observation is the motivating principle behind Top-down Dynamic Programming.

Rather than starting at the simplest sub-problems and working up, top-down starts with the biggest problem and recursively targets which sub-problems it will need to solve in order to know the final answer.

The result will look similar to our search operation but is guided by the memoization structure to improve upon its asymptotic guarantees.

Reflect upon our recurrence for the Changemaking problem:

Let’s observe how we can use this starting now at the bottom-right corner of the memoization structure:

Filling in this structure would give us the following result:

Because Top-down DP will still complete at most every table entry, its computational and space complexity are still bounded above by for the given number of rows and columns in the table.

Comparing Strategies

We’ve seen two strategies to Dynamic Programming: bottom-up and top-down. Let’s further explore their similarities and differences.

Similarities

Let’s compare our bottom-up and top-down solutions to the Changemaker problem with , .

In the bottom-up approach, we complete the memoization table from top-left to bottom-right.

In the top-down approach, we perform what is essentially a “targeted-search-with-memoization” problem, in which we can depict the search / recursion tree starting at the root of the memoization structure (bottom-right corner) and then attempting to minimize the cost associated with the solution path.

The two are similar in that they both complete the necessary cells of the memoization structure to find the optimal solution by optimally solving sub-problems. It’s how they complete the table that’s different.

Differences

The primary difference between top-down and bottom-up DP is which, and how many, sub-problems get solved: top-down is selective, bottom-up is exhaustive.

| Criteria | Bottom-up DP | Top-down DP |

|---|---|---|

| Runtime - Many Overlapping Sub-problems | Most of the memoization table will be relevant, in which case completing them iteratively leads to better wall-clock time with bottom-up due to iteration. | Although completing as many or fewer cells of the memoization table, top-down may be slower in wall-clock time due to the overhead cost of recursive calls. |

| Runtime - Few Overlapping Sub-problems | Most of the memoization table will be irrelevant, in which case bottom-up wastes a lot of effort getting to the punchline. | Targeting only specific parts of the memoization structure improves efficiency if many cells remain unused, especially in larger problems. |

| Space | Fills whole table, solves all sub-problems, taking up maximal space. | Fills only those table entries that are required, but the space is still reserved for the whole table. |

Summary

Use bottom-up when lots of sub-problems need to be solved, top-down when fewer.

Comparisons with Search

At face value, top-down DP looks a lot like how we formalized and then solved the changemaking problem with a search tree — and in a lot of ways, they’re the same!

The key differences:

- Often, we cannot easily construct the memoization structure for a search problem, and so must rely on the search space’s exploration via the tools of previous lectures.

- Even if we can, sometimes it’s just too large to realistically memoize using the structured table (since, even using top-down, memory is reserved in the table whether or not we’re using that slot).

- Using graph search to solve most top-down DP problems is a roughly equivalent technique, though can also be guided by heuristics in the case of A*.

Summary

Use Dynamic Programming when you can structure the memoization and will need it for a lot of overlapping sub-problems; use search when you can’t, or the search can be guided to avoid much overlap.