Note

Much of the content from these notes is taken directly or adapted from the notes of the same course taught by Dr. Andrew Forney available at forns.lmu.build.

Introduction

So far, in our formalizations of problem solving and search, we have made some assumptions about the environment that are not necessarily generalizable. Moreover, we have been discussing uninformed search strategies. Uninformed search strategies are essentially “blind” to problem-specific information that may not only improve runtime performance, but can actually lead to more optimal solutions! Recall our search example from last lecture in which we were searching for a path to get our agent to its goal in a grid-world.

Question

What are some ways we can loosen the constraints on the search problem to make it more generalizable?

Some ways we can loosen the constraints on the search problem include:

- Non-uniform cost: certain transitions can be more costly than others.

- Multiple goal states: there may exist multiple goals in the environment that are considered solutions to the problem.

- Possibly No Solution: a well-formed problem may have no possible solution to it!

Problems with Uninformed Search

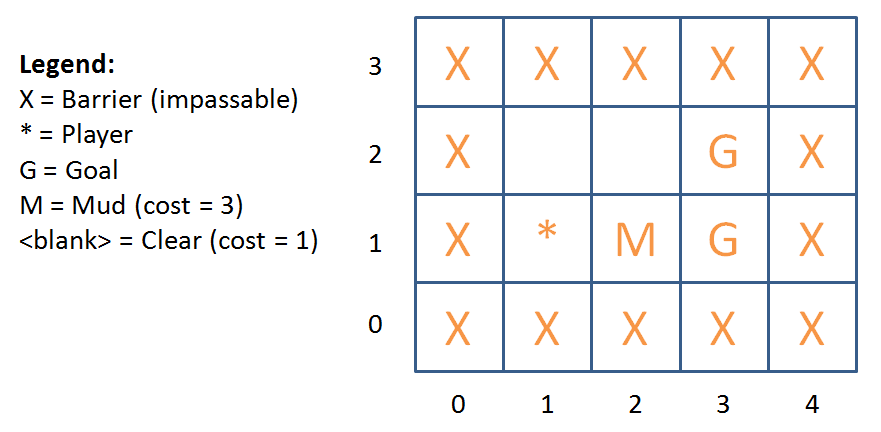

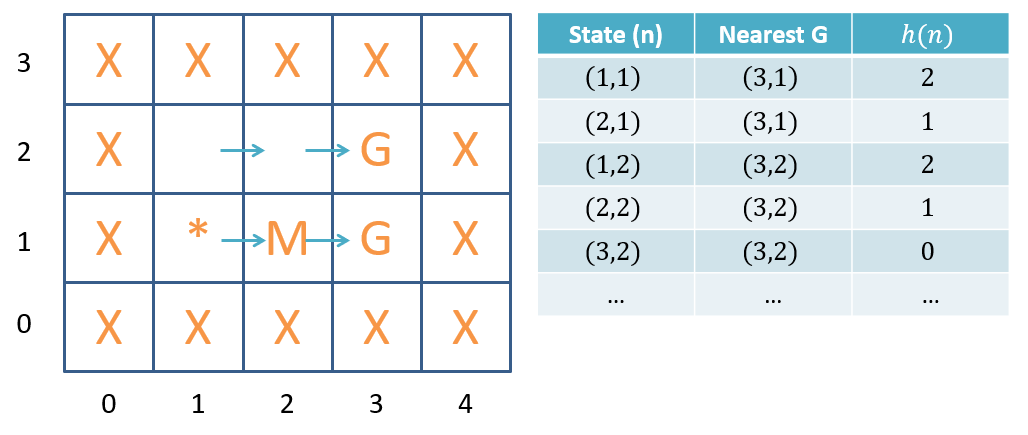

Suppose our agent must now be able to navigate mud tiles, , such that the cost of stepping on a mud tile (it’s sticky, after all) is rather than the standard for movement onto a regular tile. Moreover, there may be multiple goals to which our agent can navigate to satisfy the problem (see figure below).

An example of a grid-world with mud tiles and multiple goal states.

An example of a grid-world with mud tiles and multiple goal states.

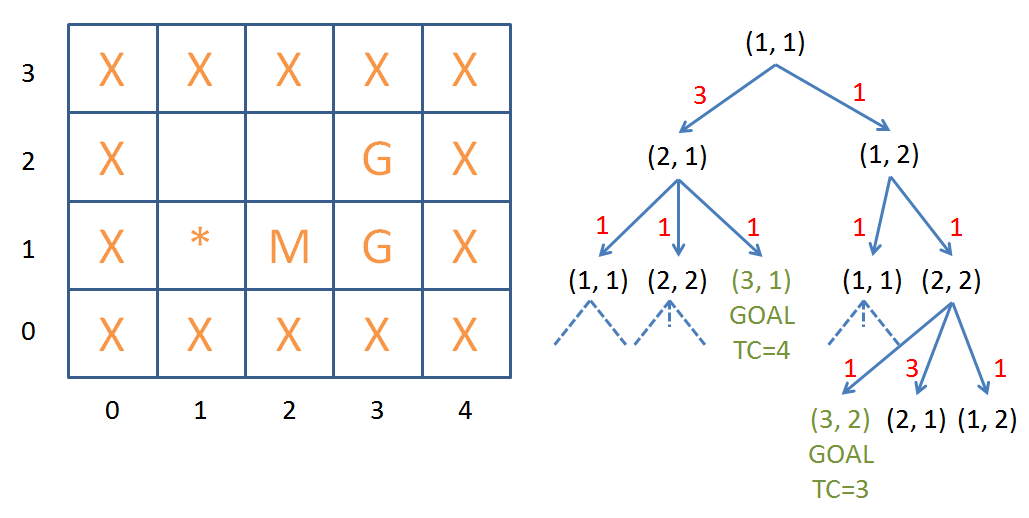

Consider how our uninformed searches would perform on the above scenario, using the search tree that each might generate.

Search trees generated by uninformed search strategies.

Search trees generated by uninformed search strategies.

Question

In the figure above, is the optimal action always the most shallow (i.e., smallest depth) in the search tree?

No! With uniform cost problems, this is the case because depth is equivalent (or uniformly proportional) to cost. With non-uniform cost problems, however, a single step may have a cost that is greater than the sum of all other steps in the tree!

Question

Will any of our uninformed search strategies (DFS, BFS, or IDDFS) be optimal?

No! None of the uninformed search strategies are guaranteed to be optimal in this scenario.

Danger

Problem 1: Uninformed search strategies that consider only a set order of expanding nodes may not be optimal for non-uniform cost problems.

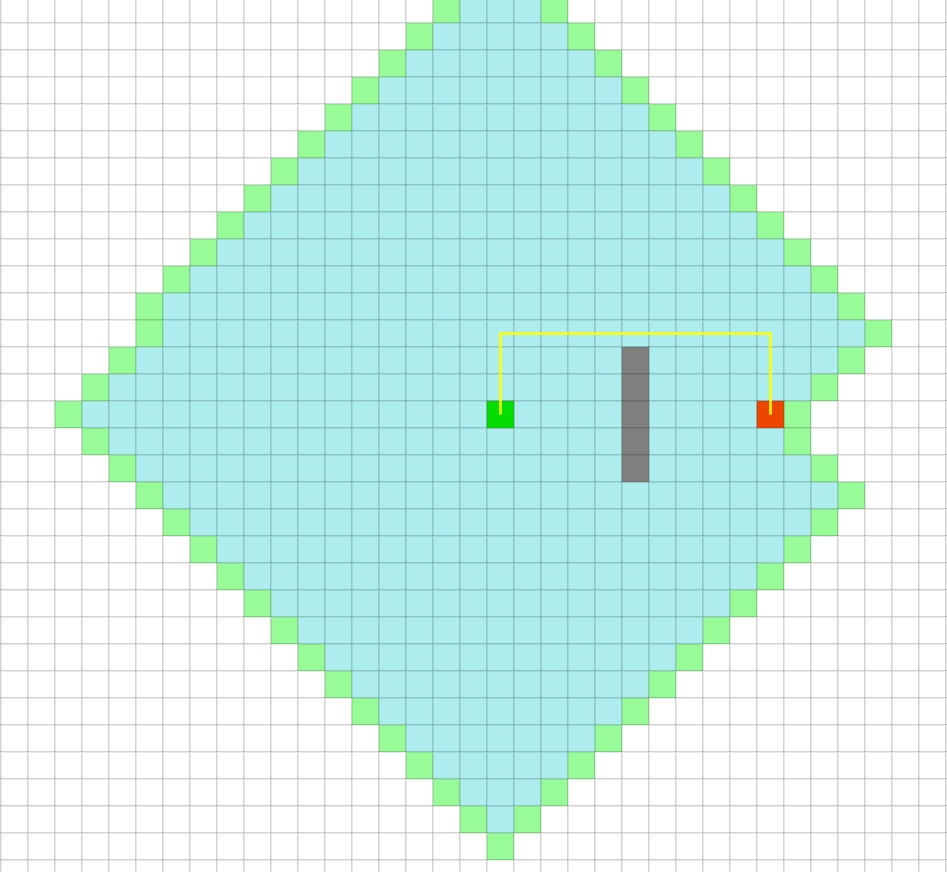

We’ll have to find a way to take these differing costs into consideration! Let us also consider a separate issue: Algorithms like BFS can be very wasteful in finding the route from the initial to goal state (see figure below).

BFS is wasteful in finding the route from the initial to goal state.

BFS is wasteful in finding the route from the initial to goal state.

Observe all of the tiles that were explored North, South, and West of the initial state. These are wasteful explorations caused by the naivety of our uninformed search — it’s simply striking out in all directions without regard for some moves being more likely successes at finding the goal than others.

Danger

Problem 2: Uninformed search strategies may perform many wasteful explorations.

We want to take advantage of the information we have about the problem to guide our search in a less wasteful manner.

Best-First Search

First, let’s address Problem 1: how can we empower our search to remain optimal for non-uniform cost problems? If your intuition was to take the costs into consideration, you’re right! Best-first search strategies expand nodes in order from least- to highest-cost from the initial state. In this way, we will never expand a node with higher total path cost before one with lower, thus preserving optimality guarantees. To accomplish this, we need to make two tweaks to our existing search strategies:

- We need to record an extra piece of information at each node in the search tree.

- We need to modify our frontier to now expand in order of least- to highest-path-cost.

Question

What extra piece of information will we need to record at each node in the search tree?

We will need to record the cost to get to that node from the root. For every node , let be the history/path cost to get from the root to node . can be computed by the recursive definition:

where is the action that transitioned from . Note the difference: the cost is the transition cost, is the total cost from the root to that node .

Question

How might we modify our frontier to now expand in order of least- to highest-path-cost?

We’ll make it a priority queue, using as the priority associated with each node. This way, we can keep track of the node with the least path cost and expand that node first in each iteration.

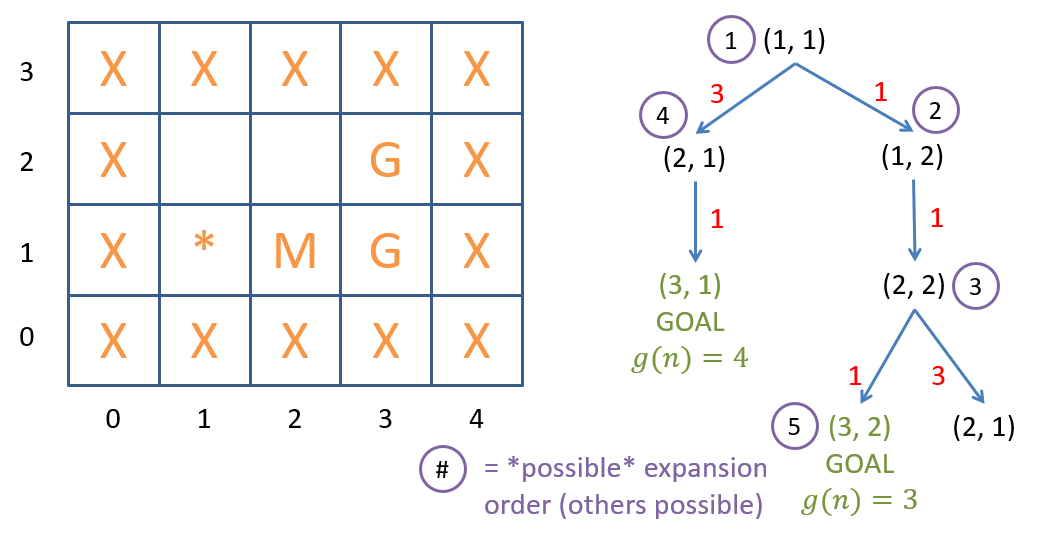

Let’s trace the execution of best-first graph search on our example (see figure below).

Best-first search on a grid-world with mud tiles and multiple goal states.

Best-first search on a grid-world with mud tiles and multiple goal states.

Some notes on the figure above:

- You should manually verify/step through the scores to see where we get the order above.

- Note that an alternative expansion order would have immediately found the optimal goal at expansion 4 instead of 5. The tie in priority sent us down a different path.

Informed Search

Let’s shift our attention now to Problem 2 and consider how we can empower best-first search to avoid wasteful explorations during search. As we saw with our uninformed search strategies, we don’t know about any descendants of a particular state (states reachable through some number of legal movements) without first expanding the states in between. However, just because we don’t know what states/costs might be incurred along a certain path, that doesn’t mean we can’t make educated guesses. We obtained optimality on non-uniform cost problems by considering , the path or past cost. In finding the optimal solution, however, this algorithm may still explore many extraneous states.

Tip

Idea: we can guide the search to be more efficient by estimating the future cost from some node to a goal.

In search, a heuristic is an estimate of cost that is likely to be incurred along a certain path to a solution in the search tree. Heuristics inform search strategies by providing problem-specific information that can guide the search, leading to more efficient strategies. In other words, heuristics represent our best guess for the future cost that would be encountered from a path starting at the evaluated node in a search tree.

Question

For our current maze path-finding problem, what would be a good heuristic that, when given some node in the search tree, would estimate how much cost would be incurred on the path to the nearest solution?

We can consider the Manhattan distance heuristic, which would compute the minimal number of movements required to get to the nearest goal from some node. The Manhattan distance heuristic, parameterized by some node in the search tree (given the set of all problem goal states, ), is functionally defined as:

(Note: the operator denotes that the distance returned is for the closest goal in the set of all goals .)

Manhattan distance heuristic.

Manhattan distance heuristic.

Warning

Heuristics are just that: rules of thumb! They are not always exact estimates of future cost. The exact costs will be evaluated by the search strategy when it computes .

Note in the example shown in the figure above, though the true future cost will be .

Question

How can we use this heuristic in our tree search approach?

In best-first search, we are already recording the history of costs in a node’s and we now have access to a heuristic . In each step, we can consider both of these values to decide on a node to expand. This is precisely the tactic of a widely applied informed search called A.

A* Search

A* search is an informed search algorithm by which nodes along the search tree’s frontier are expanded according to the result of some evaluation function, :

where is the history cost function and is the heuristic estimate function. In other words, A* “scores” all nodes along the search frontier according to and then expands them in a logical order.

Question

If there is some score associated with every node along the frontier, what would be a logical order of expansion for A* to perform given that we’re interested in finding an optimal solution?

A* will expand nodes in order of increasing . Because A* is just a variant of best-first search with a new evaluation function/priority for expansion, we can again use a priority queue data structure for the frontier. With these implementation details, let’s consider an example (see figure below).

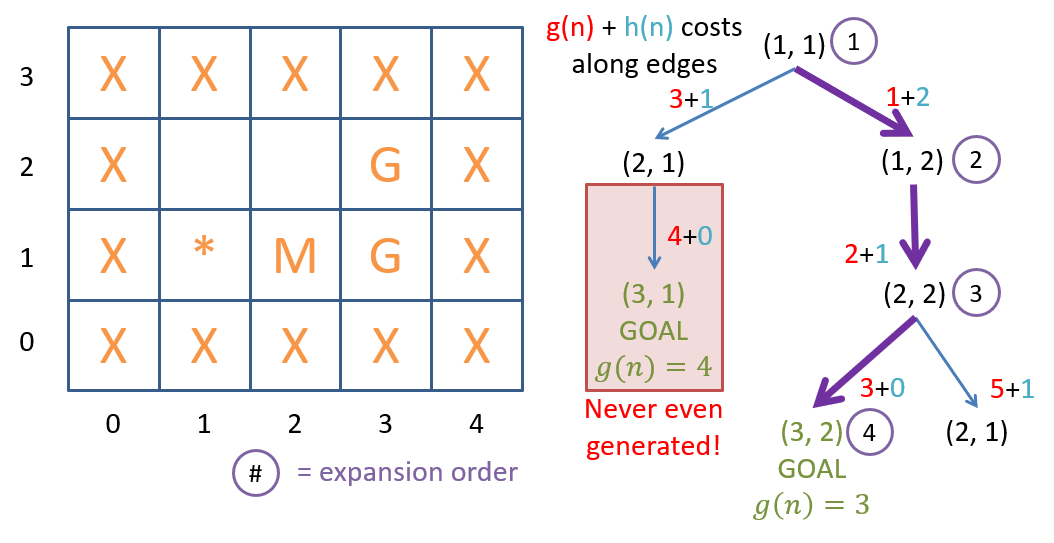

A search on a grid-world with mud tiles and multiple goal states.*

A search on a grid-world with mud tiles and multiple goal states.*

Let’s now consider the optimality and efficiency of A* search.

Question

Is A* search complete? Is it optimal?

Yes and yes! A* search is both complete and optimal.

Heuristic Design

So what, exactly, constitutes a good heuristic? Our choice of heuristic for A* search can not only affect its computational performance, but also whether or not it returns an optimal solution! We need to very carefully consider our to determine whether or not it makes good use of problem-specific knowledge to aid the search.

Question

What are some desirable traits of heuristics? What must a heuristic never do?

First, a heuristic must never overestimate the cost to a goal. Second, it should apply problem-specific knowledge. Third, it should attempt to estimate the true future cost as closely as possible.

Tip

A heuristic is said to be admissible if it never overestimates the cost of reaching the optimal goal from . Admissibility is required for guaranteeing optimality for tree search heuristic implementations.

Question

Why might an inadmissible heuristic compromise the optimality of A*?

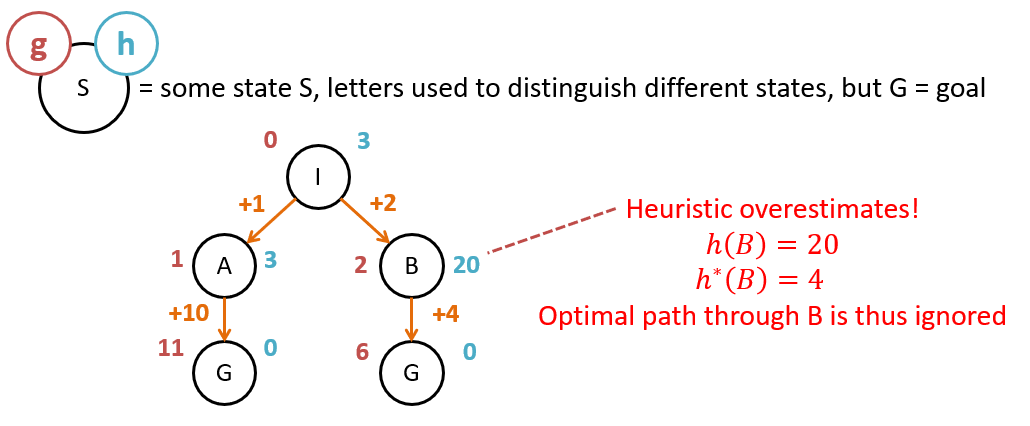

An inadmissible heuristic may compromise the optimality of A* because it may lead the search algorithm down a path with a higher true cost than the optimal path. Consider the following search tree and determine why the given heuristic is inadmissible (see figure below).

An example of an inadmissible heuristic.

An example of an inadmissible heuristic.

Question

Which of the following are admissible / inadmissible heuristics? For inadmissible ones, provide an example problem that would cause A* to find a suboptimal goal.

- (total # of goal tiles) (# of goal tiles in the same row as ) (# of goal tiles in the same column as )

- h_4(n) = \text{# of Mud tiles surrounding } n

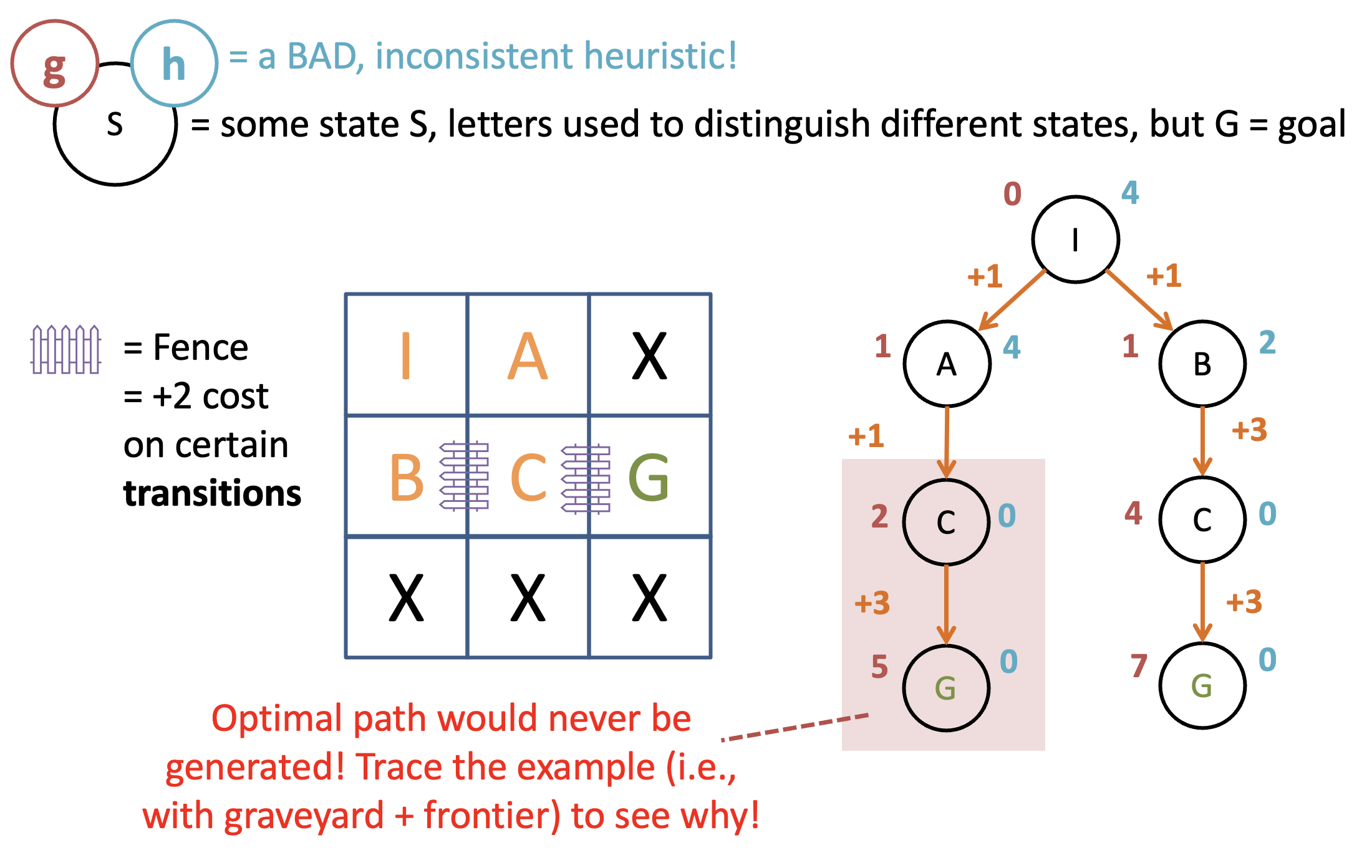

For A* graph search (i.e., tree search with memoization wherein repeated states are avoided), a slightly stronger (but same idea) criteria is required known as consistency or monotonicity. Consistency states that, for heuristic , node/state , next state reached from by taking action , , and cost of taking that action :

where is the transition cost from taking action in state and transitioning to state . This extra criteria is necessary for graph search because if we’re never expanding a previously-expanded state, we must ensure that our heuristic would not have a lower future estimate from that repeated next state than from the current one. Consider the following path-finding variant and determine why an inadmissible heuristic would cause problems (see figure below).

An example of an inadmissible heuristic in A graph search.*

An example of an inadmissible heuristic in A graph search.*

Again, consistency is required to ensure optimality by virtue of never missing a more optimal path due to the order of expansion from A*. If this is too abstract, don’t worry! You’ll have an exercise that makes this clear in the coming classwork.

The above discussion shows that not all heuristics are created equal. How, then, can we choose which to use in an implementation of A* and how effective will they be?

Heuristic Efficacy

Warning

Disclaimer: Heuristic Design is its own subfield of AI, and the below represents only the tip of the iceberg.

First, let’s define as the true future cost from to the nearest goal.

Question

Why would it be impractical to know ?

Because we would need to perform search from every state to determine its optimal future cost! We may not necessarily have the perfect future estimate, but we do have some guidelines for choosing between heuristics — some heuristic heuristics!

Question

Suppose we have two admissible heuristics , but . Which should we use, and why?

We should prefer since it will expand at most as many nodes as , but possibly fewer because it’d be closer to . Unfortunately, it’s rare that we ever have an admissible heuristic that is strictly greater than another admissible heuristic. Suppose instead we have a more realistic scenario:

Question

Suppose we have two admissible heuristics , but . How can we exploit this scenario to have the best heuristic performance?

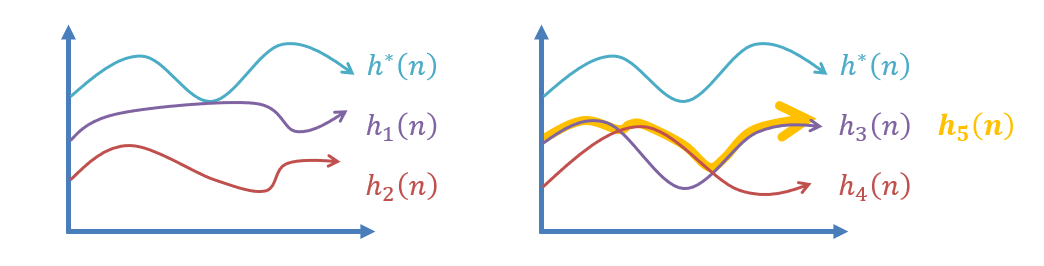

Create a third heuristic, . Note: and . See figure below for a comparison of different heuristics.

Comparing different heuristics.

Comparing different heuristics.

In other words, a heuristic that takes the maximum of two or more other admissible heuristics will always be admissible and fit our first desirable property above. However, what we have yet to address is just how to measure how well a heuristic improves performance.

Question

Suppose we did know the true future cost, , associated with every node to the nearest goal state. How could we evaluate a heuristic’s efficacy?

The difference between the true cost and a given heuristic across all states, namely: . The larger this sum, the worse the heuristic is. This is a very impractical approach, however, as we will not be able to evaluate two heuristics across every state for every problem instance we are solving. A more practical approach is to see how a heuristic performs empirically, i.e., across a wide variety of search problems in the same problem space.

Let’s think about how we might assess this empirical performance:

- The typical empirical means of assessing a heuristic’s quality is to measure how much it limits how many nodes were generated.

- The more effective the heuristic, the quicker we get to the optimal solution, therefore the smaller the search tree and thus fewer nodes generated.

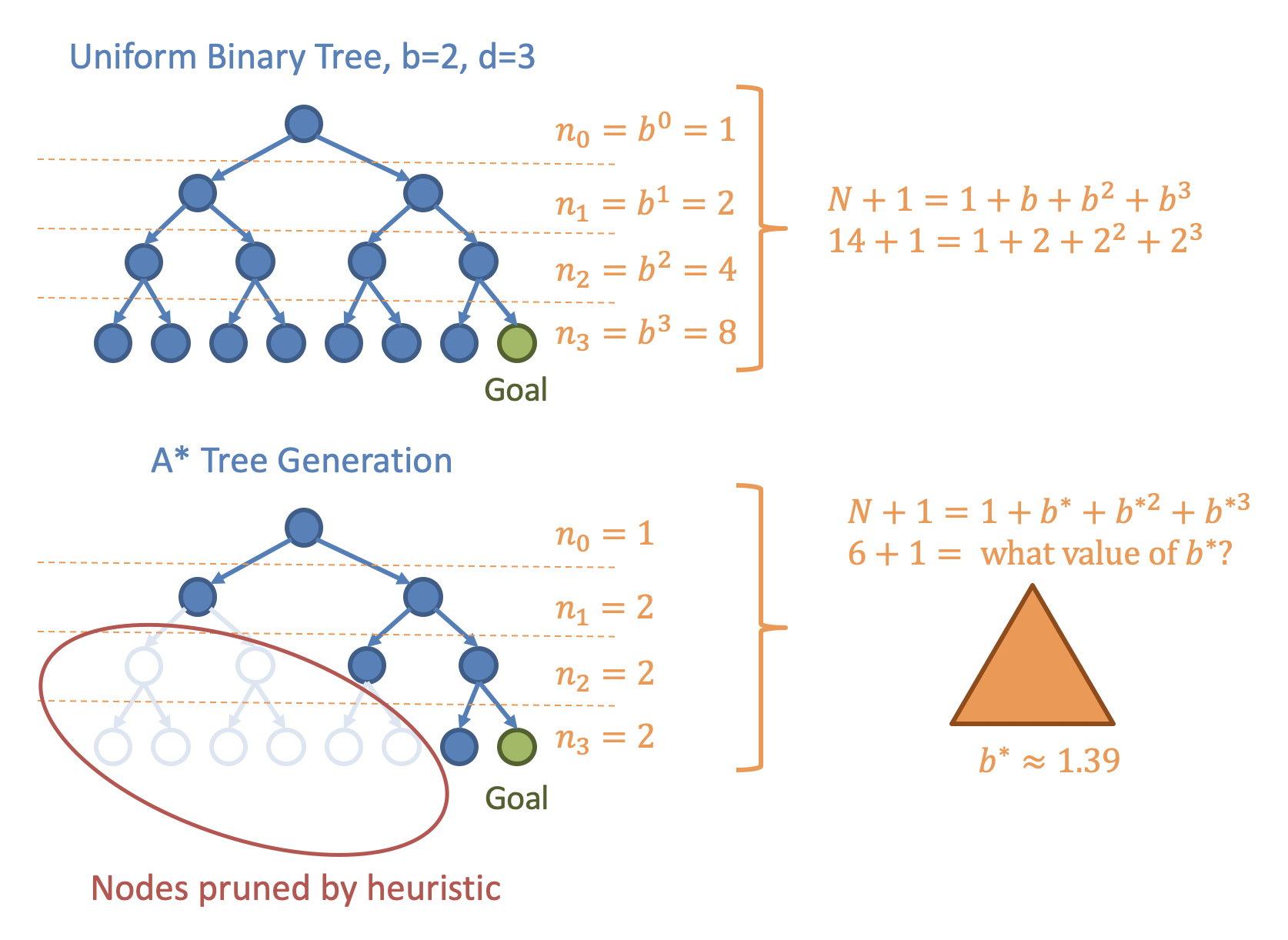

- In our previous analyses, we used the branching factor and the depth of the found goal to analyze the worst-case performance for a uniform tree.1

- The optimal goal will be at some depth , and a heuristic won’t change that. It can, however, be thought of as reducing the branching factor.

If A* generates nodes to find a solution at a depth of , then the effective branching factor, , is an approximation of the branching factor that a uniform tree containing generated nodes and with a depth of would have. has no closed-form solution, but can be found using optimization techniques such that:

where is the number of nodes generated, not including the root. To visualize this, let be the number of nodes generated at level . In a uniform tree, . For more effective heuristics, however, will be less than .

Effective branching factor.

Effective branching factor.

The space and time complexities of A* are . Note that, in the worst case, the heuristic is useless at pruning, in which case .

In practice, the value of has been observed to remain fairly constant across many problem domains. This makes computation of useful for comparing the efficacy of different heuristics on problems.

Conclusion

We have now seen a variety of different search strategies, each adding something that the last was missing. Why not skip to the end and use A* if it seems like the most capable?

Tip

Remember that there’s no such thing as a free lunch. Getting more adaptive strategies usually comes at some costs, and it’s all about picking the right tool for the right job.

Each of the advanced searches we discussed come at some cost. For example, best-first needs to track the of each node, and A* needs the of each node on top of that — neither of which you needed to record for the other uninformed searches. Moreover, remember the data-structure complexities of operations on different frontiers — insertion into/removal from a Queue or Stack is but from a priority queue is .

Tip

When should we use each type of search strategy?

Uniform-Cost Problems:

- Use breadth-first if all you care about is speed.

- Use depth-first if memory is going to be a problem (big search spaces) and there’s no chance of infinite loops/not reaching a terminal.

- Use depth-limited if we know the depth of the shallowest goal node, .

- Use iteratively-deepening depth-first otherwise.

Non-uniform Cost Problems:

- Use A* if you can find an admissible (and consistent if using graph search) heuristic for the problem.

- Use best-first otherwise. Bad/faulty heuristics will compromise the optimality of A*, and sometimes it’s just too difficult to think of a heuristic for a problem.

Footnotes

-

A uniform tree is a tree in which each level is full. ↩