Note

Much of the content from these notes is taken directly or adapted from the notes of the same course taught by Dr. Andrew Forney available at forns.lmu.build.

Introduction

Let’s reflect on what we’ve learned so far about CSPs:

- We started with naive backtracking as an adaptation of Search to solve CSPs, but these alone were computationally inefficient.

- We enhanced backtracking with domain-reducing algorithms like forward checking, constraint propagation, and heuristics like MRV and LCV.

- We improved on backtracking’s exponential computational complexity for situations where we could coerce constraint graphs into tree-based structures.

Let’s introduce a new problem to continue our discussion of CSPs: the N-Queens problem.

In the N-Queens Problem, we are given an chessboard and queens. The goal is to place the queens on the board such that no two queens threaten each other. That is, no two queens can attack each other horizontally, vertically, or diagonally.

Question

Can we use any of the techniques we’ve learned so far to solve the N-Queens problem for large values of (e.g., )?

Probably not! The computational power required to solve the N-Queens problem for such large values of would be enormous.

In this lecture, we will explore two alternative strategies that might be able to solve these huge CSPs with a high probability:

- Randomly assign variables and then repair that random assignment into a solution.

- Identify and combine the best parts of different (failing) solutions to create a successful one.

Local Search

With backtracking, we started with an empty assignment to variables and incrementally built our way to a solution through depth-first search.

Local Search is an iterative search strategy for solving CSPs (and some other problem types as well!) that is neither complete nor optimal, but can be used to find solutions to large problems when backtracking is intractable.

The steps of local search are as follows:

- Randomly assign values to each variable within their legal domain without worrying about violated constraints.

- Find the set of variables with violated constraints.

- Attempt to reassign to one of those variables.

- Repeat until a solution is found (or you give up!).

Local search is another algorithmic paradigm that, although we’ll see applied to CSPs, can also be used in a variety of different contexts.

Motivating Example

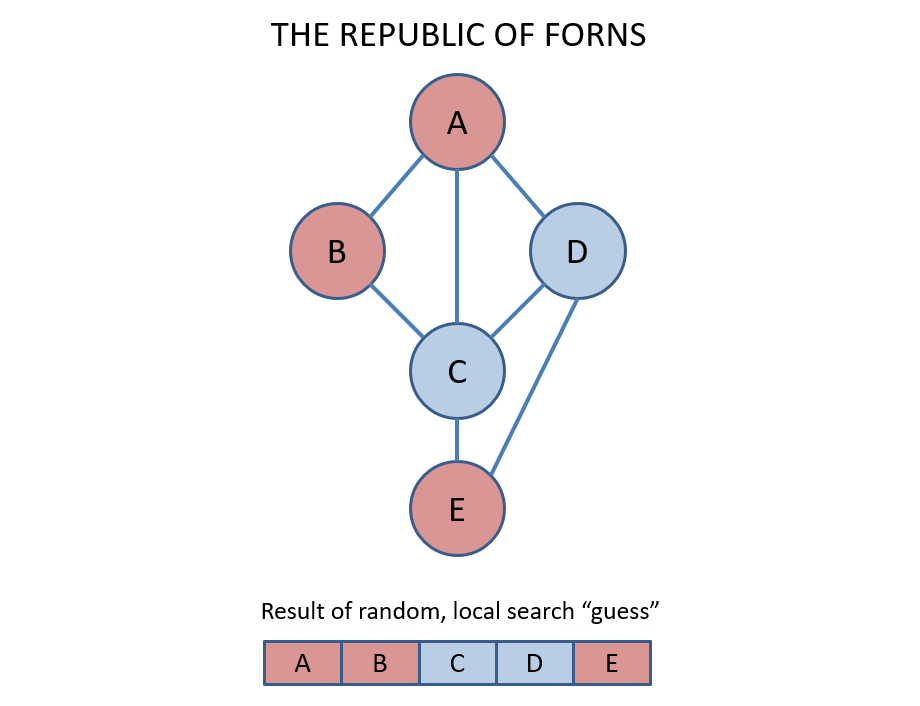

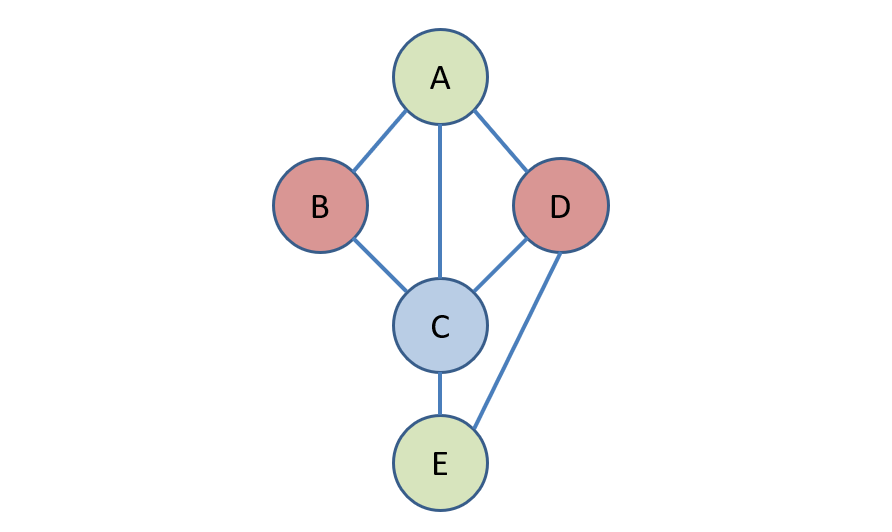

Let’s consider the Republic of Forns Map Coloring problem with colors.

Step 1 - Random Variable Assignment: Suppose we begin by assigning the following colors to the variables in the CSP; note: they do not form a solution, but are close to one.

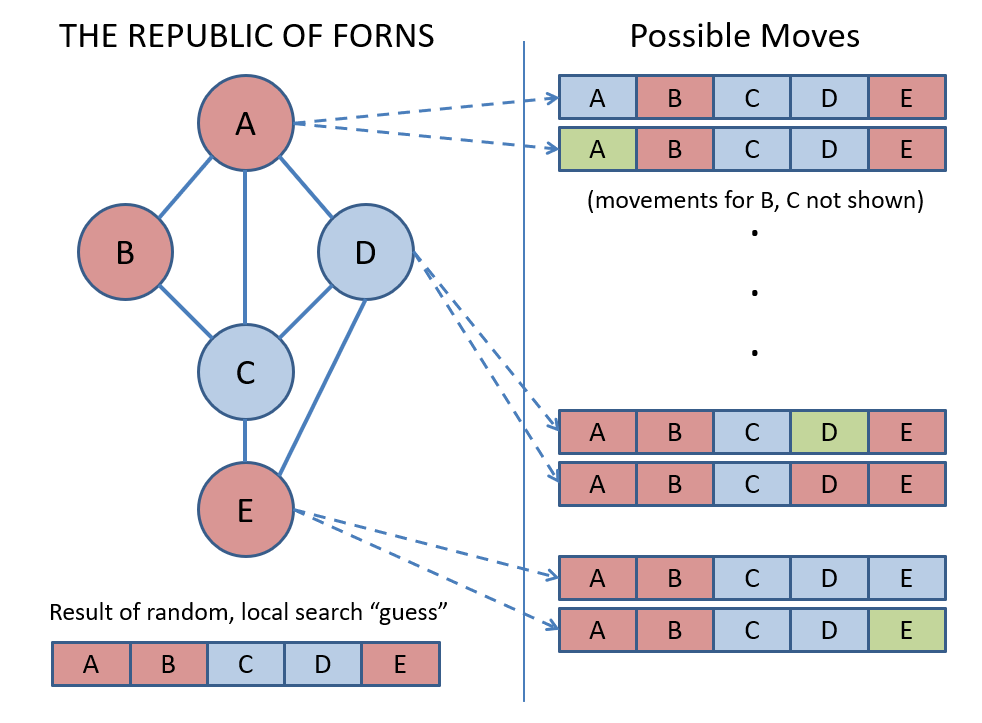

Step 2 - Select a variable with a violated constraint at random: In vanilla local search, any conflicted variable is chosen to be reassigned with equal probability.

Question

Why do we choose any of the conflicted variables to reassign rather than according to a deterministic rule (e.g., the one violating the most constraints)?

Suppose, by reassigning the most conflicted variable (call this variable ), we make another variable violate the same number of constraints (call this variable ), such that we ping-pong between assigning to and . Choosing conflicted variables at random gets us out of ruts!

In our example, we see that variables , , , and have conflicts.

Suppose we choose at random for the next part of the example.

Info

In Local Search, the set of all states that are possible from changing the value of 1 variable at a time is known as its neighborhood.

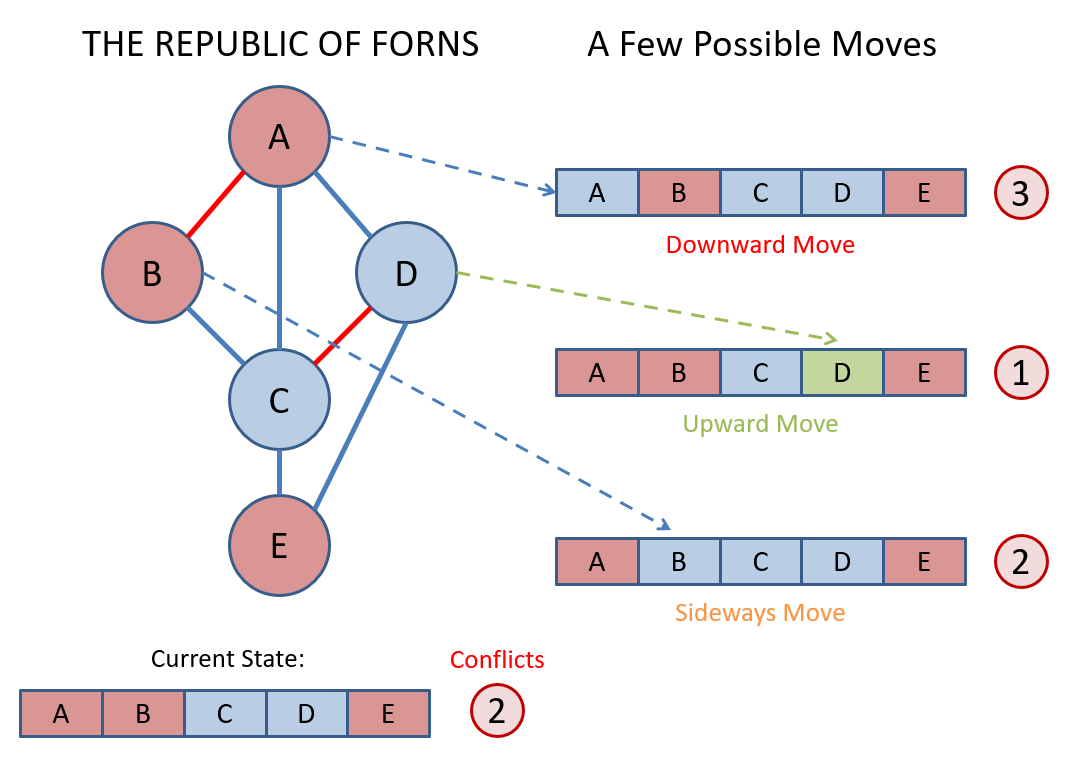

Step 3 - Reassign to the chosen conflicted variable: We choose the value for a reassigned variable that results in the fewest number of residual conflicts.

The following vocabulary is useful in characterizing the quality of a reassignment:

- Upward Moves reduce the number of conflicts before vs. after the reassignment.

- Downward Moves increase the number of conflicts before vs. after the reassignment.

- Sideways Moves keep the number of conflicts the same before as after the reassignment.

Info

The Min-Conflict Heuristic says to choose the value for a reassigned variable that results in the fewest number of residual conflicts; choose one at random in the event of a minimal tie.

Some things to note about the Min-Conflict Heuristic:

- Reassigning a variable may not reduce its conflicts to 0, but this is normal. The hope is that over many iterations, the conflicts will be resolved.

- The Min-Conflict Heuristic attempts to only take actions that improve the quality of some assignment (or at least, does not damage the quality of some assignment) iteratively.

In our example, assigning results in the fewest number of conflicts afterwards.

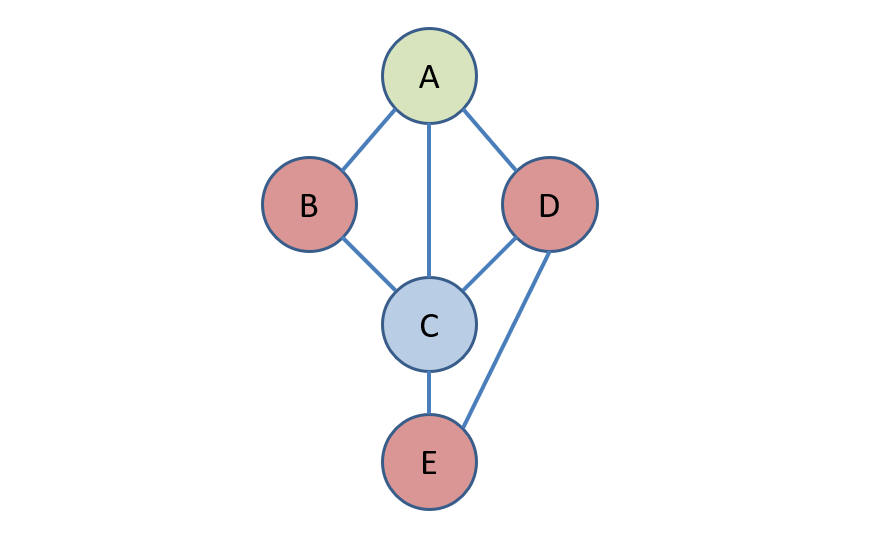

Step 4 - Repeat steps 2 and 3 until a solution is found. Suppose we next chose to reassign conflicted variable and assign it a value of .

We would have to finally assign a value of in a future iteration as well.

Some things to note about the procedure and example:

- We were able to find a solution with fewer assignments than there are variables (if you don’t count the original random assignment).

- The result here is not unique.

Local Search Characteristics

Question

Compared to backtracking, does local search demand more or less space/memory?

Local search demands much less space/memory than backtracking.

Local search is an iterative solution that operates only on a single state representation, as opposed to managing a recursion tree with a potentially large call stack and many local variables allocated along the way.

Without making any assumptions about the problem, local search does not have any optimality or completeness guarantees.

However, empirically, local search has been shown to have near constant-time performance for even massive CSPs!

The performance of local search depends on the ratio between the number of variables and constraints in the CSP.

Performance degrades sharply in a small area around what is known as the critical ratio between these two cardinalities.

Exactly what this critical ratio is depends on the specific CSP being solved.

Question

Why do you think performance is better on either side of the critical ratio?

On the left, there are fewer constraints than variables, meaning there are likely to be fewer conflicts overall to resolve.

On the right, there are fewer variables than constraints, meaning that the variables are so constrained that zeroing in on the smaller solution space becomes easier.

Hill-Climbing

Now that we have a better understanding of local search, let’s think about how to proceduralize a couple of ambiguous steps from the general Local Search definition above.

Info

An objective function decides the quality of some state by a problem’s specification. Sometimes called its value, a state can be evaluated by something like the min-conflict heuristic or other such heuristics.

Question

What would make a good objective function for CSPs that scores how good an assignment is?

The number/percentage of constraints satisfied!

The objective is to satisfy all of the constraints, but we can also interpret some states as being closer to satisfying those constraints than others.

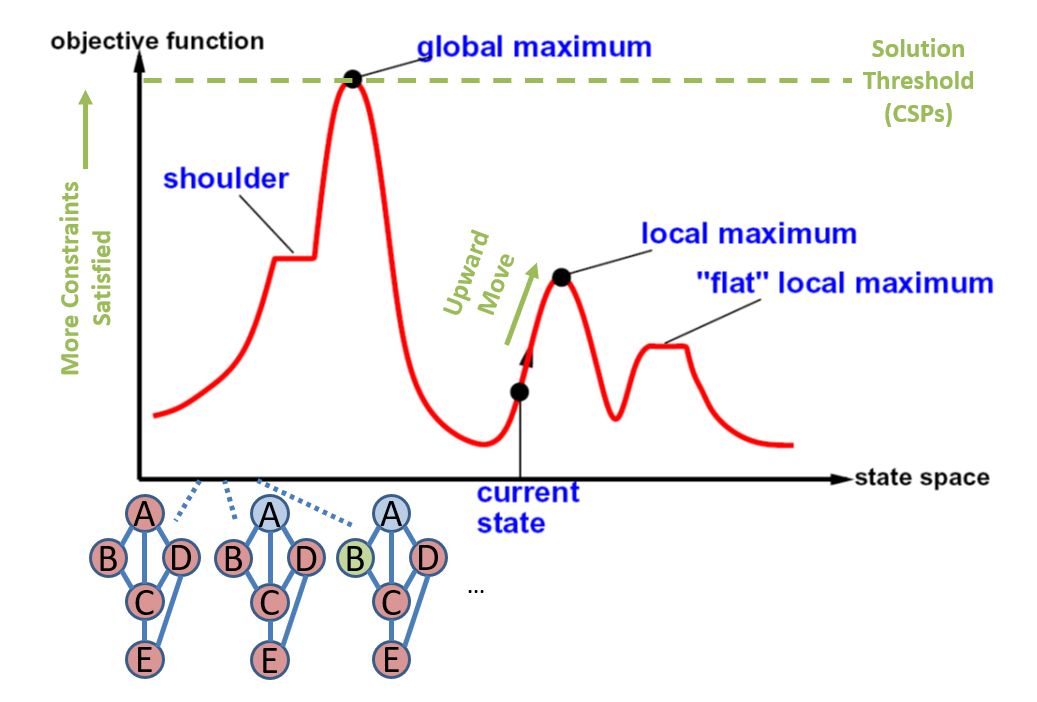

See the figure below for an example of an objective function for a map coloring problem.

Warning

The drawing above is for intuition only and is a flattened, 2-D version of what the neighborhood of a map coloring problem could look like. In reality, the curve would be in many dimensions that can’t be drawn on the page!

In the figure above, the current state is one that might be encountered after a random guess or after a modification of the state. Each move (a reassignment to one of the variables) can be classified as an upward, sideways, or downward move (up the hill, across a plateau, and down the hill, respectively).

Different local search strategies are characterized by how they navigate the so-called objective function hills.

The most basic local search strategy is a greedy approach called Hill Climbing: always take the best move until you can improve no more!

Algorithm: Hill Climbing

1. s ← pick a random initial state

2. while s is not a solution:

3. n ← highest value neighbor in neighborhood(s) (like by min-conflict)

4. if n is a lower value than s:

5. return s

6. s ← n

7. return s

Question

What is the issue with naive hill-climbing approaches, and can you suggest a simple fix to overcome it?

Naive hill-climbing approaches may get stuck at a local optima! Once a local optima is reached (i.e., there are no more upward moves available), we can simply try again.

Info

You can think of Hill Climbing as scaling a mountain in the fog — you know which way is up and which is down, but you don’t know if you’re scaling Everest or an ant-hill.

Hill Climbing with Random Restarts is a hill climbing approach such that, whenever a local maxima is hit and a solution is not yet found, the agent will restart from another randomly initialized state and try again.

Restarting might sound like a waste of time, but it can actually be a very effective technique.

One difficulty with random restarts is that it might be challenging to determine when we are at a local maxima vs. the global maxima.

Its biggest weakness is that it gives up very easily once it’s hit a local maxima — even if this happens to be only a few downward moves away from a global maxima!

Question

Can you propose an improvement to Hill Climbing (even with Random Restarts) that may help ameliorate the weakness described above?

Make it willing to accept some downward moves, though control how likely it is to do so as the search iteration continues.

Simulated Annealing

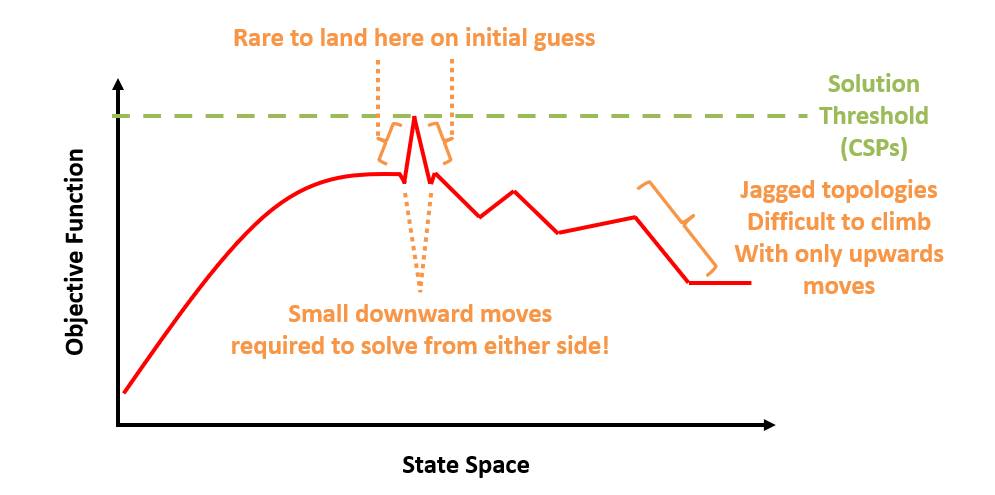

Consider the following curve of some CSP’s objective function, and suppose we are using local search to find a solution.

Question

Where will most of our random starts for local search begin on this problem? What’s the problem with those likely start locations?

They’ll likely start on the large curves on either side of the global optima, and the problem is with the tiny dips on either side of the slope leading to a solution, which hill climbing would fail to overcome.

The idea behind Simulated Annealing is to sometimes take downward (seemingly worse) moves to get unstuck at these kinds of “local optima”.

The term annealing comes from the process in metallurgy of heating a metal and then gradually letting it cool to harden and temper.

Question

What relevance do you think annealing has to the problem we’re discussing?

While the metal is hot, it’s more malleable and can be shaped and changed more easily. As it cools, however, it becomes more rigid and less likely to change.

Similarly, in simulated annealing, we start with a high probability of taking downward moves, but gradually decrease that probability over time/moves. This way, we can escape local optima and still settle on a solution by the end of the search.

There are two primary components of simulated annealing in application to enhancing Hill Climbing:

- Temperature: some number that decides the probability of taking a downward move (higher = more likely).

- Cooling Schedule: decides the rate at which the temperature decreases between iterations.

Simulated annealing during hill climbing proceeds in several steps:

Algorithm: Simulated Annealing

1. s ← pick a random initial state

2. temperature ← some starting temp

3. while s is not a solution AND temperature ≠ 0:

4. n ← pick a random next state in neighborhood(s)

5. if n is a sideways or upwards move:

6. move to n

7. if n is a downward move:

8. only take it with some likelihood proportionate to temperature

9. reduce the temperature

10. return s

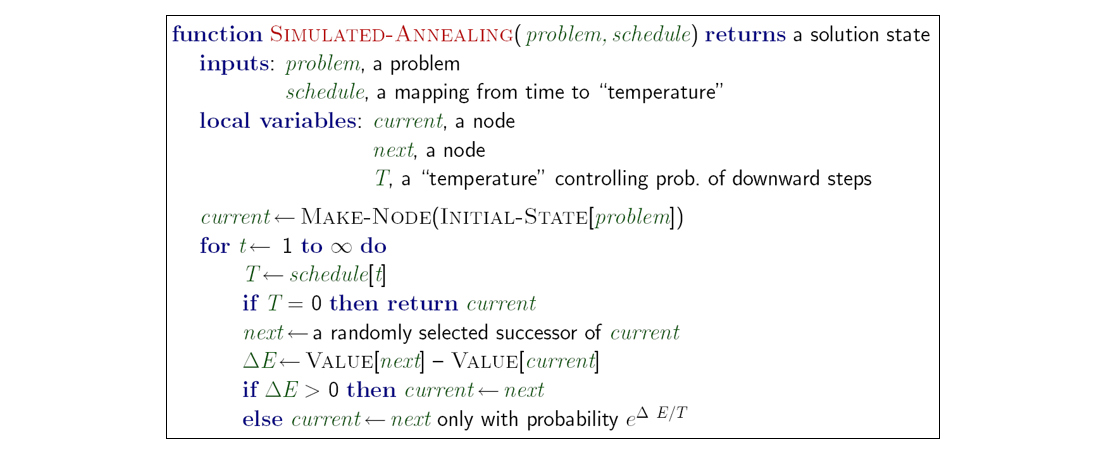

See the figure below for the algorithm as presented in your textbook.

Info

Intuitively, adding simulated annealing to your local search can help it overcome hiccups in the objective function curve that naive hill climbing may almost never be able to solve!

Watch this YouTube video for a visualization of simulated annealing on a more realistic 3D optimization surface with a “flipped” objective function (lower = better).

Some notes on the video:

- Each dot is another state traveled to at a new iteration.

- The color of the dot is the temperature, with red dots being hot (high likelihood of taking downward moves) and blue dots being cool (low likelihood).

- The optimal solution is found at the end (the lowest position on the surface).

Note how, as the temperature decreases, the algorithm is less likely to take worse (upward) moves, and more likely to take better (downward) moves.

Genetic Algorithms

The last algorithmic paradigm we’re going to discuss is inspired by biology: Genetic Algorithms.

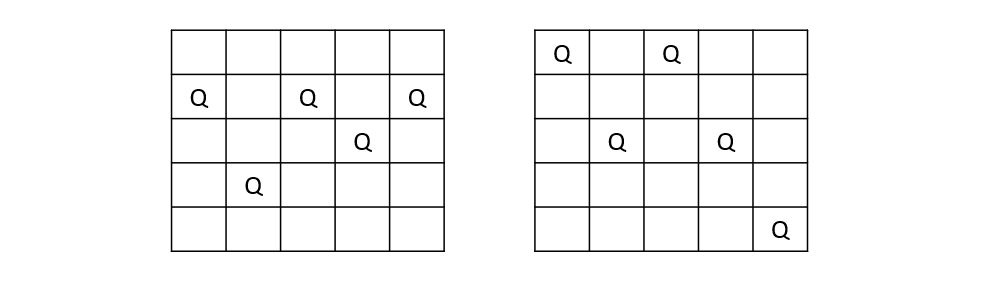

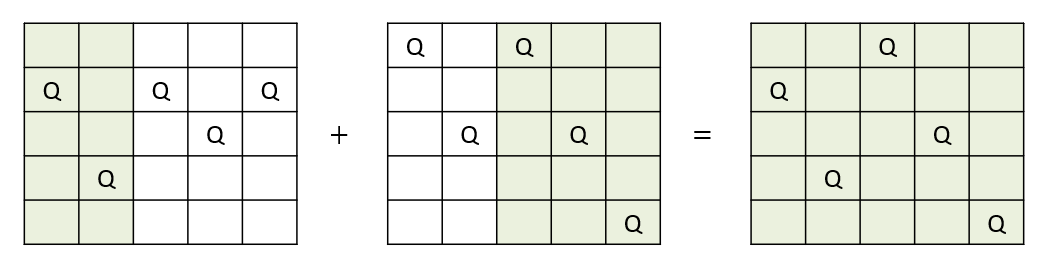

Consider the following two (incorrect) instantiations of the 5-Queens problem.

Some things to observe:

- Parts of each board state are correct/conflict-free, and other parts are not.

- Between the two, there exists a perfect solution.

Suppose we had a strategy that attempted to take parts of two (incorrect) states in an attempt to create a new one from their pieces.

Question

What biological process does this mimic?

Evolution!

Artificial Evolution

Genetic Algorithms represent another algorithmic paradigm in which solutions can “evolve” through procedural selection.

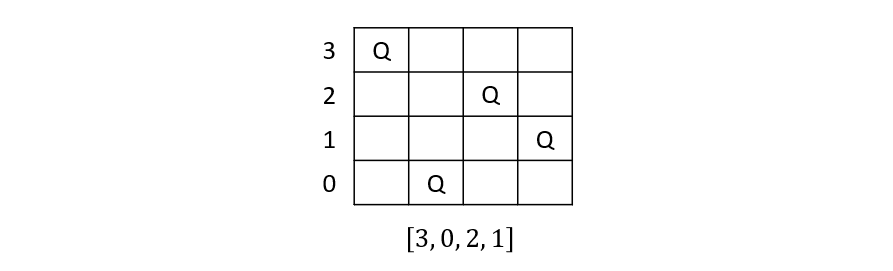

The first step is to express the states of these problems in gene-like sequences.

Consider the N-queens problem in which, assuming each queen is placed in a different row by index in a vector, the states can be represented as vectors of column placements.

For example, the 4-Queens problem can be represented as shown below.

With these defined, we can then specify how to “evolve” them into working solutions.

Genetic Algorithms are iterative, proceeding in sequential generations until either a solution is found or some stopping condition has been met. They are specified by several key components:

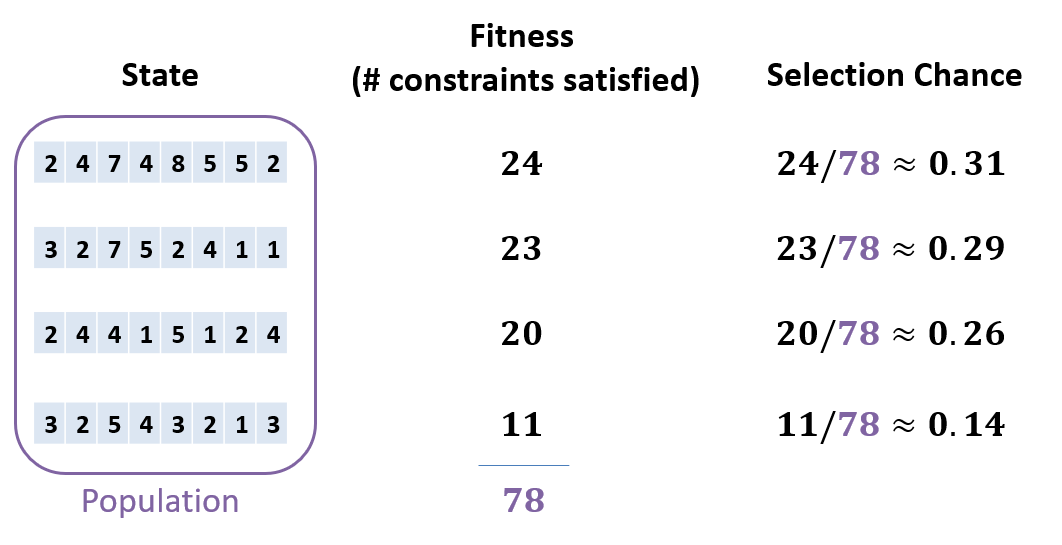

Component 1: Fitness and Selection: a Fitness Function/Score is the objective function from local search that decides the quality of a given state. A higher fitness means that it is more likely to be selected for mating.

Question

What would be a good fitness function for the N-Queens problem?

The number of constraints satisfied! The more that are, the more fit that state is.

Consider the following states on the 8-Queens problem in which each has a fitness score according to the number of constraints satisfied, and a selection percentage proportionate to its fitness over the total population’s fitness.

Selection: For a population of size , create pairs by selecting mates based on their selection likelihood (flip an -sided biased coin).

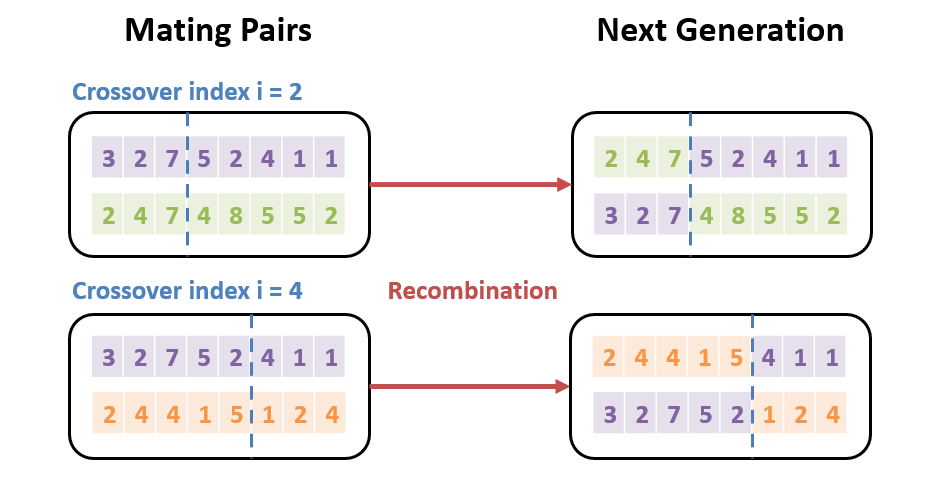

Component 2: Recombination: once mates have been chosen, a new generation of “offspring” is created through a recombination of parent states/traits.

For the N-Queens problem, this can be done by choosing an index from which each mating pair creates a pair of “crossovers” with the property that, for parents , child 1 = and child 2 = .

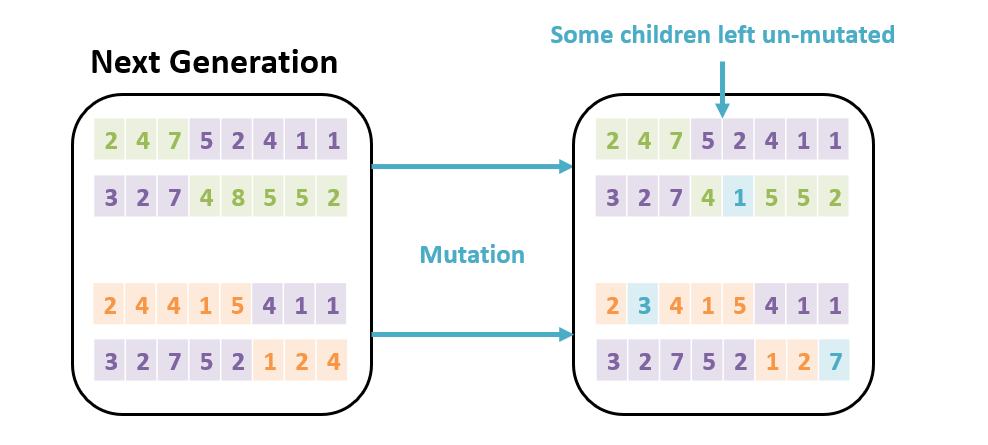

Component 3: Mutation: In order to avoid getting stuck in local maxima, there is also some chance that each crossover in the new generation may have a small mutation to its genetic structure.

Once mutated, we have a whole new generation to test for a solution. If none exists, we start all over again — a story as old as humankind, literally!

Applications

Genetic Algorithms are neat because they mimic biological processes.

Warning

Genetic Algorithms are a niche technique and are often misapplied. With more modern advances in AI, they are well-suited for a shrinking number of applications.

Still, they can be used as a strategy for a variety of problems:

- Simulating biological processes.

- CSPs wherein there may be many local optima but few global optima (mutation can help “jump” to better problem states).

- Some engineering applications and optimization problems.

- Refining agents in competitive settings (literal survival of the fittest).

Some game-playing agents (e.g., Google’s Alpha Star) use Evolutionary Algorithms at some level of abstraction to help produce adaptive agents at large-scale games like StarCraft II!

Watch this fun video that shows genetic algorithms being used to make little box cars!