Note

Much of the content from these notes is taken directly or adapted from the notes of the same course taught by Dr. Andrew Forney available at forns.lmu.build.

Introduction

Recall from the last lecture that we discussed the concept of constraint propagation as a means of improving backtracking by limiting the domains of variables, thus reducing the branching factor of the search tree.

Question

What are some other ways of reducing the amount of backtracking work required to solve CSPs?

Some possibilities include:

- k-consistency: Rather than verifying node () and arc () consistency, including through forward checking and constraint propagation, we could consider checking consistency between some node domains, and incrementally increase until we had our original number of nodes. While this is an interesting idea (and describes a class of algorithms), we will not examine it in this course.

- Ordering Heuristics: The order in which we choose to assign to variables and the choices of values to assign during backtracking can dramatically influence the performance of the CSP solver.

- Exploiting CSP Structure: The format of a given constraint graph can lead us to some shortcuts in solving it, and identifying these becomes a huge time saver.

Ordering Heuristics

We’ve hinted at how the order in which we explore assignments to variables can matter, so let’s now examine how and why.

We can start with a little intuition: assignments that restrict the domain of a variable are “more likely” to lead to a failure because there are fewer options left to explore.

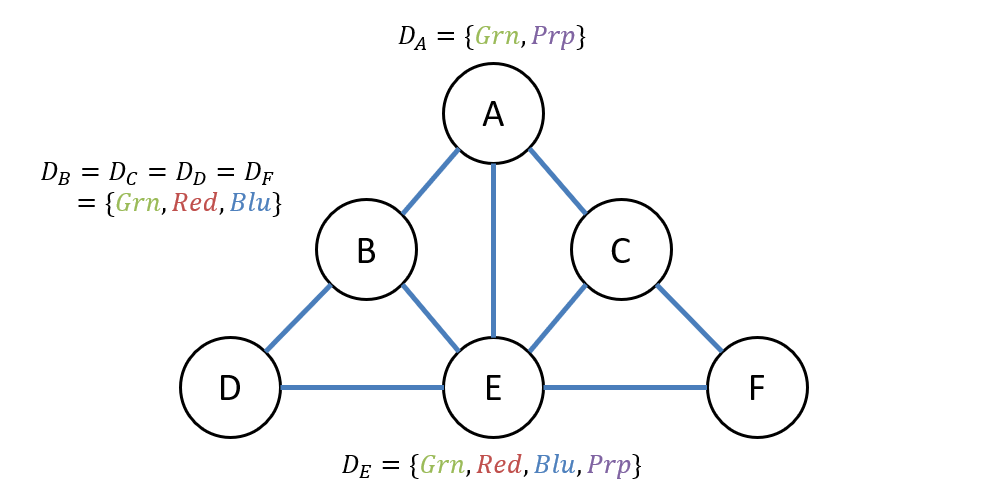

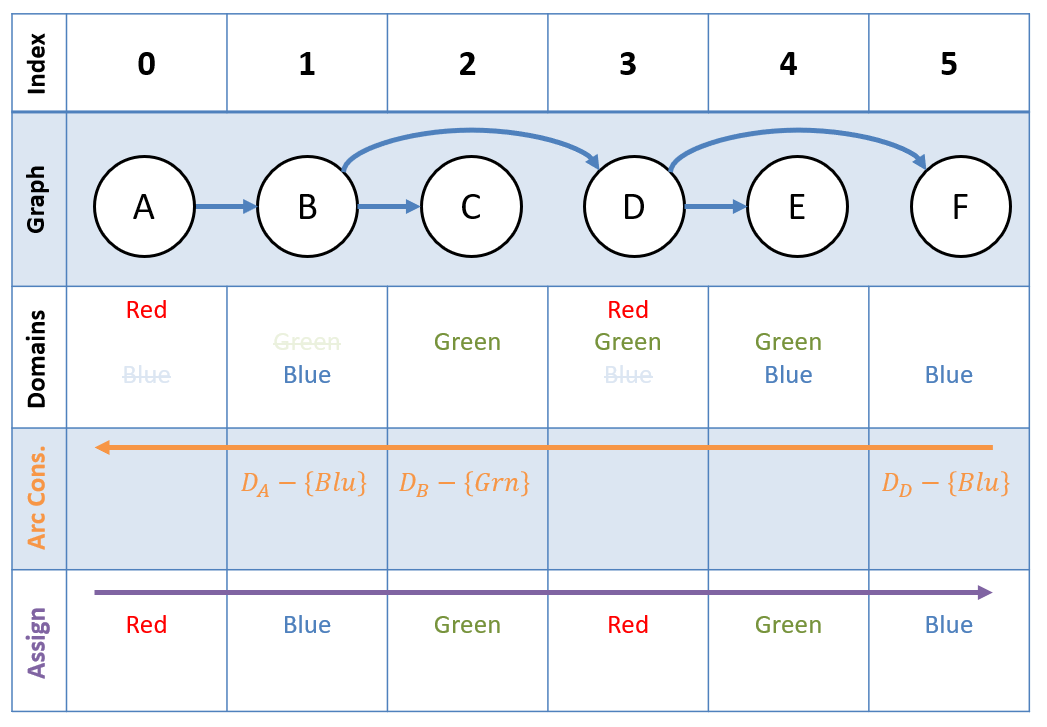

Consider the following constraint graph associated with the Map Coloring problem on 6 variables with different domains.

Question

Given the choice of first assignment, which variable should we assign to first during backtracking? Why?

We should assign to variable first since it is the most at-risk of having no assignable values later in the process!

This is a cheap and easy heuristic to compute since we can assume having instant access to all variable domain cardinalities:

Info

Ordering Heuristic 1 - Minimal Remaining Values (MRV): The MRV heuristic stipulates that, during backtracking, the variable with the smallest domain should have priority assignment over variables with larger ones.

This changes the backtracking algorithm from having a fixed variable assignment order, to one that is dynamically chosen at every stage of the assignment.

The MRV heuristic is sometimes referred to as the “Most Constrained Variable” Heuristic, and ensures that any failures that would be caused by variables with smaller domains occur sooner in the backtracking than later.

The idea is to avoid reaching a state at which a variable has an empty domain, and there is a higher likelihood that (through assignment) we exhaust a smaller domain before a larger one.

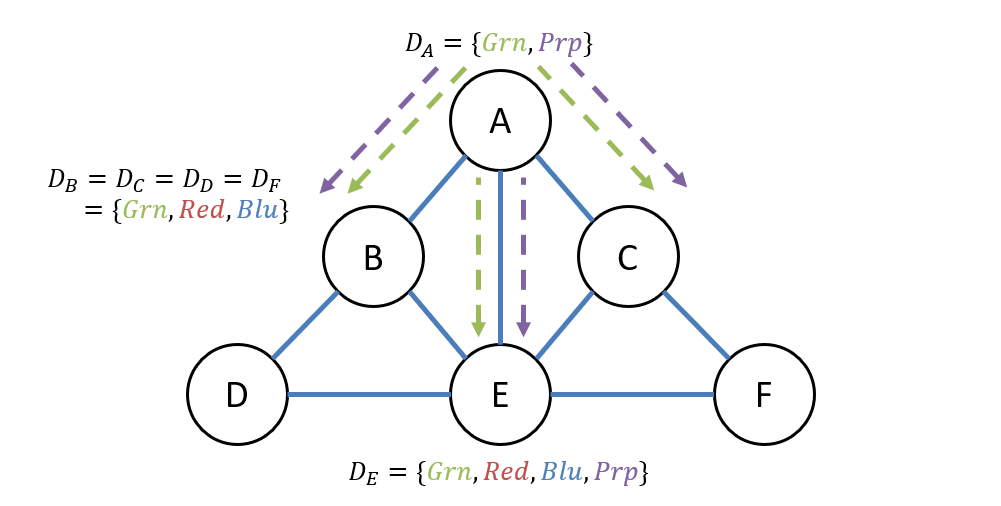

Suppose now that we decide to start with variable in our example above; let’s consider another question.

Question

Choosing variable , there are two values in its domain we can attempt to assign next; which should we try first and why?

We should try Purple first because it least-limits the domains of connected variables!

Info

Ordering Heuristic 2 - Least Constraining Value (LCV): Given a variable chosen for assignment, attempt to assign its values in the order of least-to-greatest values removed from other domains.

This entails doing at least one step of look-ahead to determine the impact of assigning each value.

There is no such thing as a free lunch! LCV, when applied on large problems, can save an enormous amount of work, but it also involves doing at least one step of look-ahead to determine the impact of assigning each value.

Exploiting CSP Structure

So far, we’ve seen how we can use ordering heuristics to improve the performance of CSP solvers. Now, let’s think about how we can exploit key parts of the structure of a CSP to improve performance.

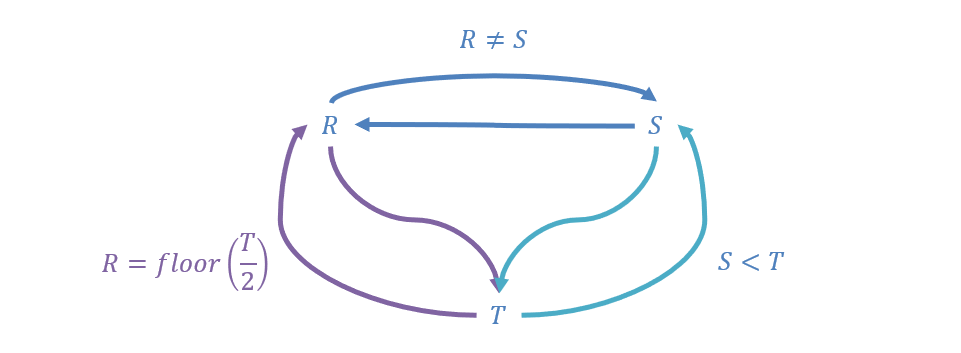

We’ll motivate these structural concerns with our three-variable CSP.

Problems like the one above require constraint propagation due to the presence of cycles in which assignments/domain restrictions to one variable may iteratively affect the others, circularly.

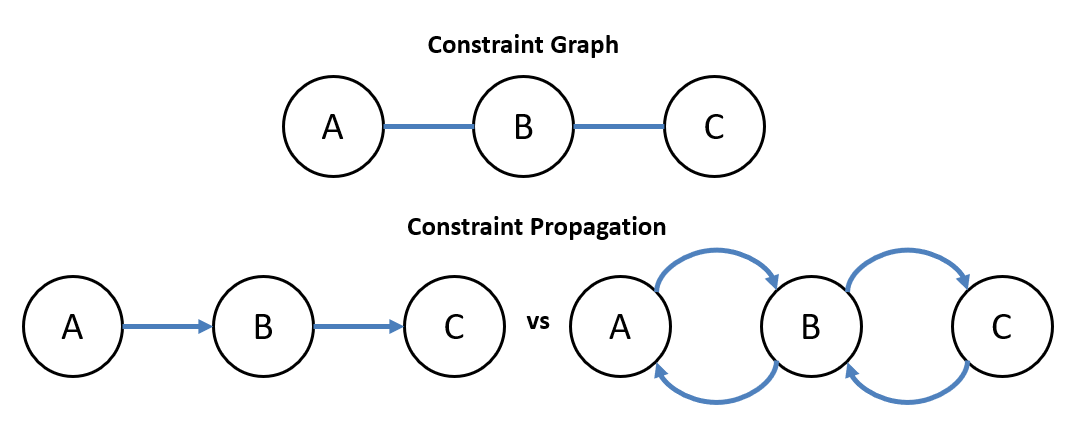

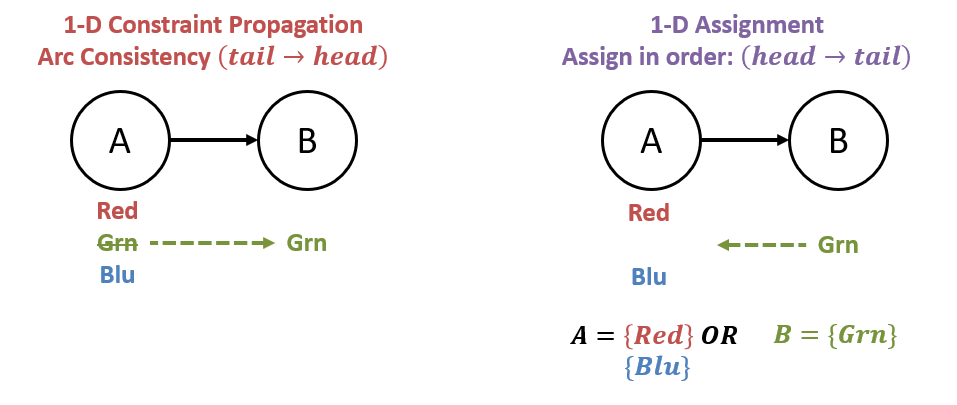

Now let’s consider a three-variable CSP constraint graph, and determine whether or not we need to consider both arcs from any two variables in constraint propagation.

Question

In the constraint graph above, do we need both directions of arcs from each connected variable during constraint propagation, or could we get away with just 1? Why?

We can get away with just one direction if we assign to variables in the opposite direction, because then each assigned value will find at least one value that is consistent with it!

Info

A useful property of constraint graphs without cycles: constraint propagation need be only unidirectional with assignment done in the opposite direction.

Enforcing arc consistency from to ensures that when we assign to , we are guaranteed that at least one of the remaining values in will be consistent with the assignment.

It turns out that this exploit doesn’t apply to only linear constraint graphs, but also to a more general data structure: a tree!

Exploiting Tree-Structured CSPs

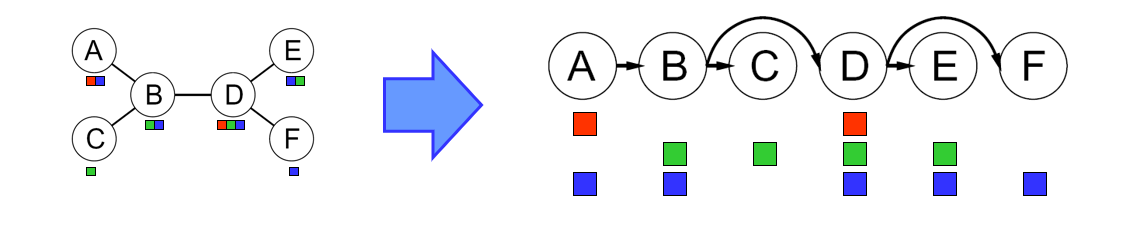

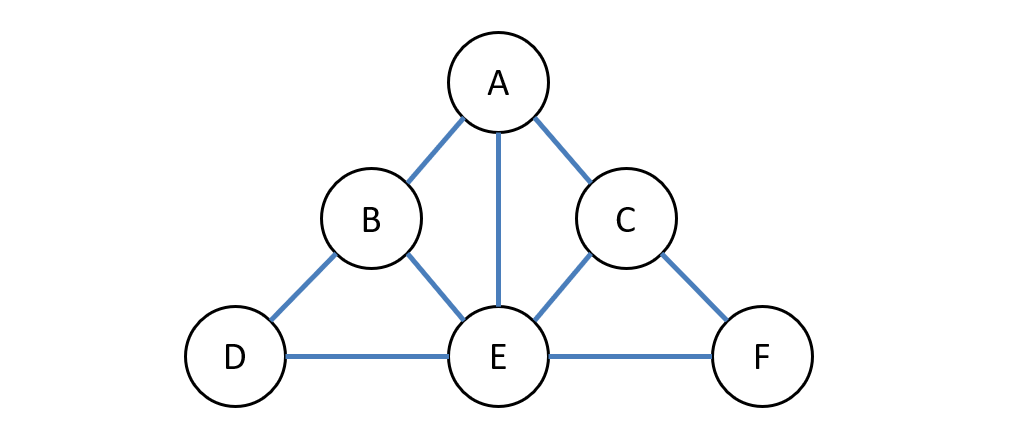

To see the utility in tree-structured CSPs, consider the following example of the Map Coloring problem with some pre-restricted domains.

Some things to note about the example above:

- Take a moment and convince yourself that this is indeed a tree structure. It need not be a binary tree, but if you imagine picking up this graph at the chosen root and then letting the other nodes dangle by gravity, you can see the tree structure shake out.

- This “tree-ization” of the graph is not unique! We could have just as easily have chosen or any of the other variables to be the root so long as there are no cycles in the graph.

- Once a root is chosen, the edge directions can be chosen by a breadth-first traversal starting at said root.

Using this “tree-ified” constraint graph is now a breeze, and proceeds in three steps:

- Index Each Node: Assign some index to each of nodes in breadth-first ordering, starting with at the root.

- Bottom-up Constraint Propagation: Propagate constraints from leaves of the tree upwards to root .

- Top-down Assignment: Assign values to nodes that are consistent with parent’s from .

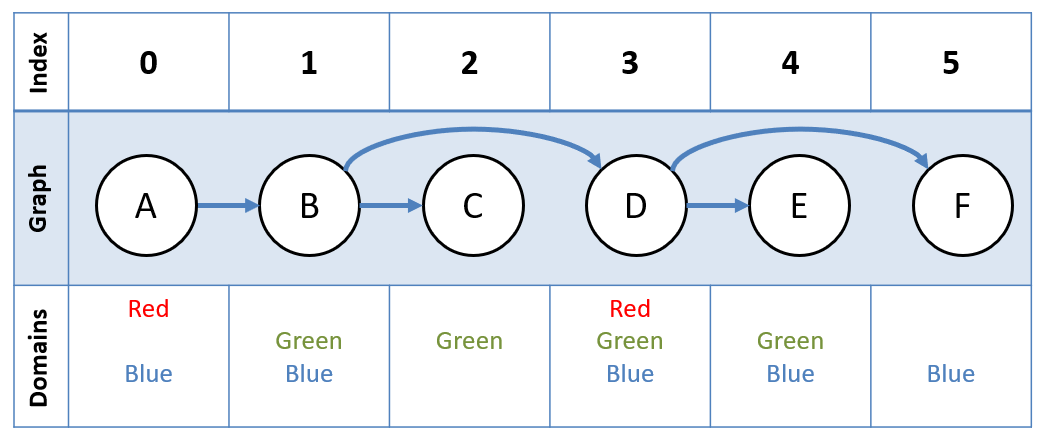

Step 1 - Indexing

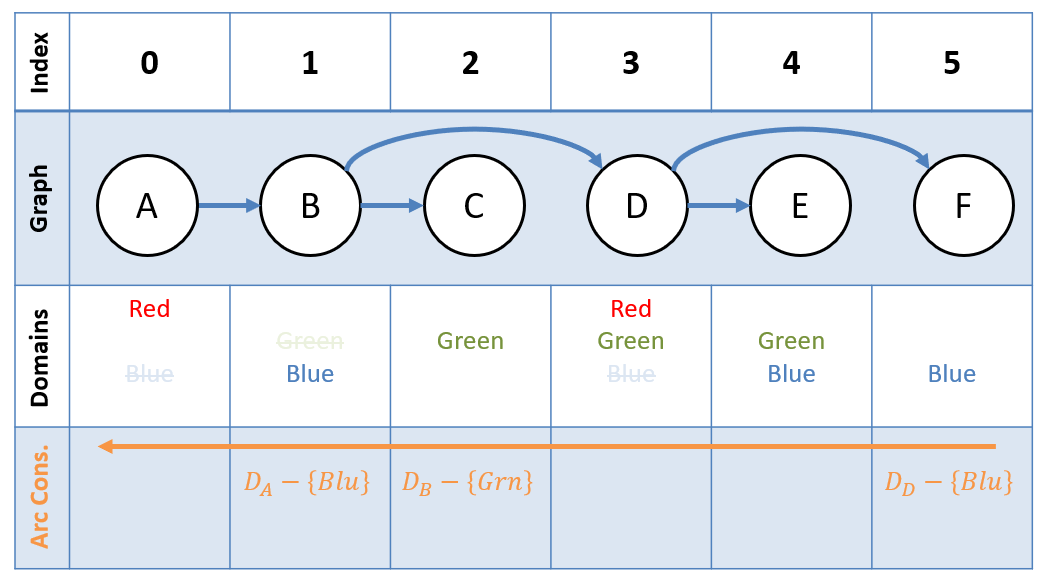

Step 2 - Bottom-up Constraint Propagation

We’ll start with , then, for each inbound arc in descending index order, ensure arc consistency.

Step 3 - Top-down Assignment

Start with , then, for each outbound arc in ascending index order, make an assignment that is consistent with the previous.

Question

Given the procedure above, in terms of the number of variables and the domain size of each (assuming, for simplicity, uniform domains) , what is the computational complexity of CSP solvers for tree-structured constraint graphs?

The computational complexity of CSP solvers for tree-structured constraint graphs is , since ensuring arc consistency between any two variables is a operation, and that is performed once for each of the variables.

It’s important to note that this procedure relies on the constraint graph being tree-structured, which it won’t always be.

Cutset Conditioning

To recap:

- Arbitrary CSPs have a solution complexity of due to the DFS behavior, even with heuristic improvements.

- Solving tree-structured CSPs is a much more manageable , but not all CSPs are tree-structured!

Question

Can you think of a strategy to compromise between these extremes for solving arbitrarily-structured CSPs?

One strategy is to massage them into tree-structures! As we’ll see, this can work for some nearly-tree-structured CSPs.

To motivate this technique, consider the following constraint graph and observe how it is nearly-tree-structured.

Question

In the CSP above, how do you think we could somehow make solving this more tree-structured?

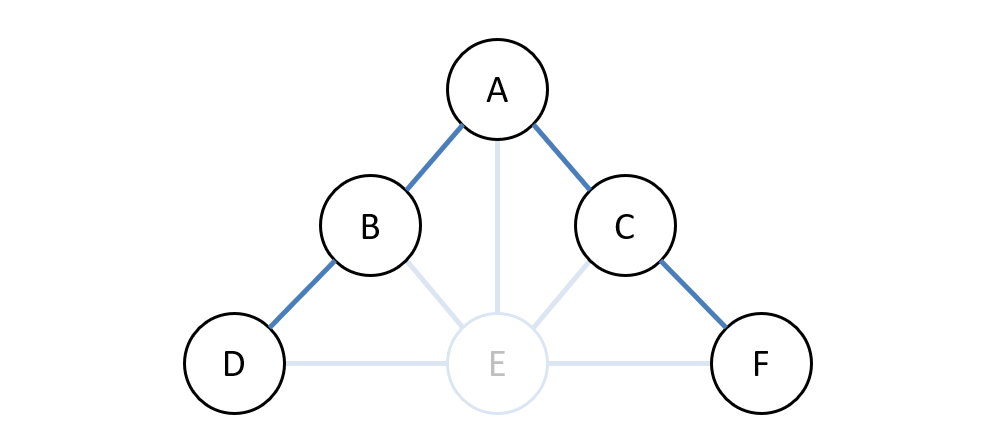

We could consider variable separately from the rest, then solve the others with removed.

Note how the remaining variables are indeed in a tree-structure, and can be solved much more easily than if we were to use a naive approach.

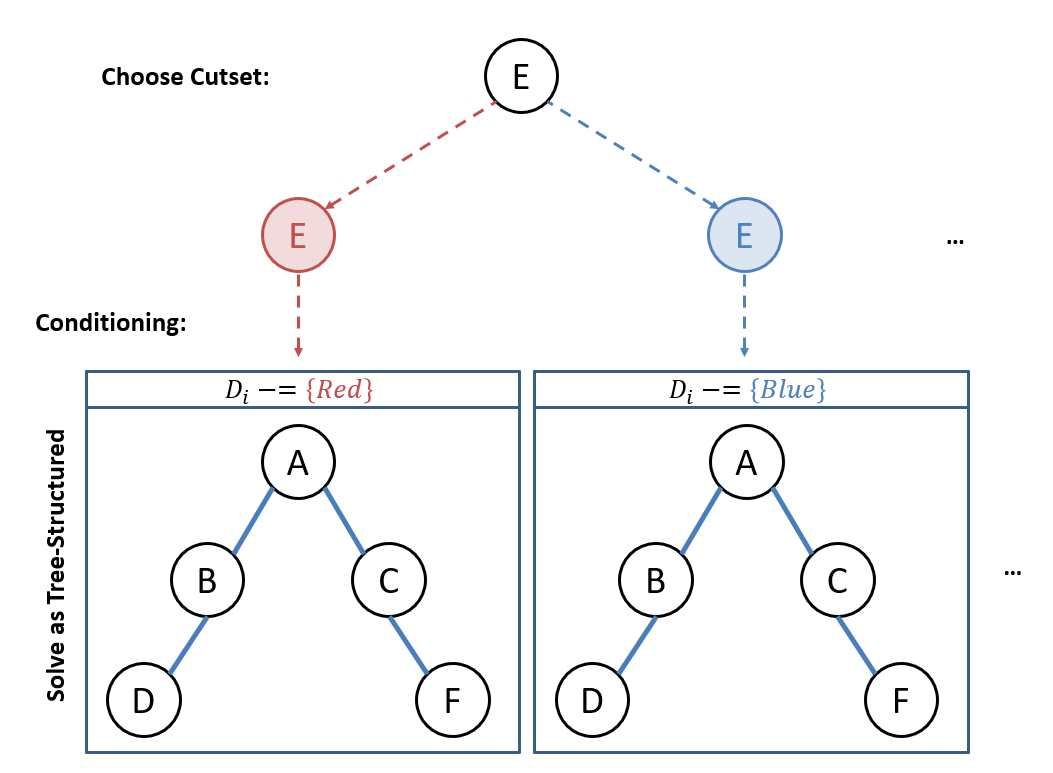

Cutset Conditioning

Cutset Conditioning is a technique for solving nearly-tree-structured CSPs in which some variables are assigned to separately from the rest, removed from the constraint graph, and leaving a tree-structured CSP for those remaining.

- Cutsets are some set of variables that are cut (severing edges) from the original constraint graph and solved separately.

- Conditioning is the process of assigning a value to some variable in a cutset, performing forward checking on its neighbor domains before cutting, and finally, severing it from the original graph.

Cutset Conditioning works in three steps:

- Choose some cutset(s) of variables that leaves a remaining graph that is tree-structured.

- In traditional backtracking fashion, condition on the cutset.

- Solve the remaining tree-structured CSP.

Some notes about Cutset Conditioning:

- There are algorithms to select the cutset, but we won’t be discussing those here.

- We could do this for multiple cutsets during step 1.

- For cutsets of size , the complexity becomes a very manageable

- There are other structure-based CSP solvers as well, but we’ll stop with cutset conditioning.